For a decidedly ironic example, look at Miller Brewing Co.

The company was founded in Milwaukee in 1855 by one of America’s early brewing giants, a German immigrant named Frederick Miller. His family would run the company for more than a century, proudly weathering Prohibition and emerging as a brewing powerhouse in the 1950s with one of America’s iconic brands, Miller High Life. Then the company was sold to a chemical manufacturer, which flipped it to a cigarette maker, which unloaded it on a London-based brewing conglomerate, which merged its operations with two of its biggest competitors, Molson and Coors. Today, its biggest seller is Miller Lite, a thoroughly modern brand (triple hops) on whose jazzy vortex bottle you will find not a single mention of the brewery’s history.

A mega-corporation with no regard for heritage? Big surprise.

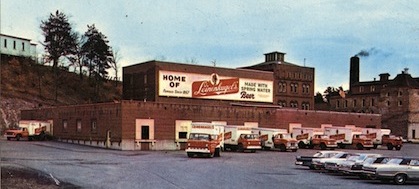

But then chew on the Jacob Leinenkugel Brewing Co.–a prototypical heritage brewer, a survivor run by the founder’s fifth-generation descendants who produce beer made from 19th-century recipes, proudly labeling its brand as “the Pride of Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, since 1867.”

And, yep, wholly owned by Miller Brewing.

When Miller acquired Leinenkugel’s in 1988, it transformed the company. In less than 10 years, what had been a quirky brewery serving mainly Wisconsin and Chicago would triple its production and expand its reach throughout the entire nation. It’s tempting to shrug off the brewery as just another corporate cog, except that its president, Jake Leinenkugel, insisted, “We don’t take orders well from the parent company. We do what we think is right for the Leinenkugel family brand.”

That ethos is the product of the most transformative period in American brewing history, a period that “My father called a mode of survival rather than thriving,” Leinenkugel said.

Before World War II, beer was mainly a localized industry. Though pasteurization, refrigeration and improved long-distance transportation had been around since before Prohibition, it was still costly to ship beer from, say, St. Louis to Los Angeles. These so-called shipping breweries had to recoup their costs somehow – and their solution was pure marketing genius—introducing the Premium Beer.

Yes, Budweiser, Pabst, Miller all tasted about the same as, say, Rheingold or Lucky Lager or Neuweiler. But by calling themselves premium, their makers were able to charge a dime more per bottle than the locals.

“The premium image was such a strange phenomenon,” said F. M. Scherer, former chief economist for the Federal Trade Commission who’s written extensively about post-war changes in the beer industry. “It’s all-important, yet it hardly makes any sense.”

Premium beer wouldn’t have shaken up the industry much, except, in Scherer’s words, “some bad stuff happened.”