Drafting A Revolution

An Inside Look at the Pioneering Days of American Craft Beer

Humble Beginnings

One American had taken similar advice to heart years earlier, his epiphany striking in a Boots drug store in Glasgow, Scotland.

Jack McAuliffe had been a Navy mechanic on the Polaris nuclear subs stationed in nearby Holy Loch. Good with his hands—his mother taught him to sew at age 3 and he had apprenticed to a welder while in high school in Fairfax County, VA—McAuliffe realized that if he wanted to make the richer, tastier beers he was used to in Scotland once he shipped out he would need to make them himself. “Bam!” he thought in that Boots in late 1966. “That’s how I’m going to do it.”

McAuliffe bought a kit for 5 gallons of pale ale, plus a plastic trash can that would serve as primary fermentation vessel for what became the initial original batch of the American craft beer movement. It was McAuliffe, after another epiphany during a tour of the Anchor brewery a few years later, who would open the first new craft brewery in the U.S. since Prohibition.

While Maytag’s exertions at Anchor were Herculean, McAuliffe’s at what he came to call New Albion, after the superannuated English name for Northern California, were masochistic.

First, he had to win over partners. Jane Zimmermann, who was pursuing a career as a therapist, and her friend Susie Stern, recently arrived in Northern California from Chicago to study music at Sonoma State, each put up $1,200, impressed by the enthusiasm of the young Navy vet with the square jaw and sharp blue eyes. (And Stern suspected that McAuliffe, who raised an additional $2,600, also appreciated the utilitarianism of the old Dodge van she’d driven into town.)

The trio then faced the challenge of slicing through onerous red tape. Who had heard of a new brewery license? Especially for a small concern in the middle of nowhere? (McAuliffe had rented part of an old fruit warehouse off Eighth Street East in Sonoma wine country, more by happenstance than any calculation: he had been living in the area, working as a contractor.)

State officials would often refer to New Albion as a “winery” on official forms, which unspooled that much more red tape to correct. Finally, on Oct. 8, 1976, the New Albion Brewing Company was incorporated. Seven months later, on Saturday, May 7, at 3 p.m., the company hosted “the Consecration of the New Albion Brewery,” with an after-party nearby. It proved rare time off.

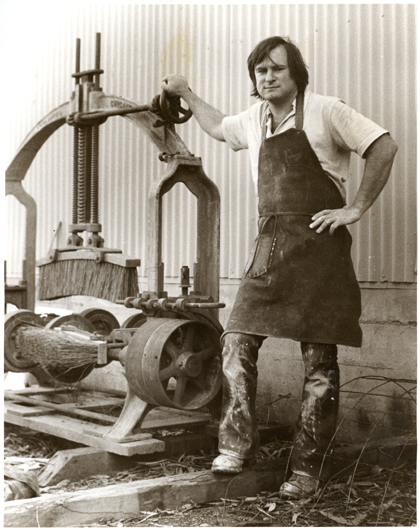

McAuliffe, especially, had spent 12- to 16-hour days building out the old fruit warehouse into a working commercial brewery, scrounging for parts—there were no suppliers of smaller-scale brewing equipment common today—and moving spider-like as he built a gravity-flow system that could eventually produce a barrel and a half, or roughly 495 12-ounce bottles, at a time.

In fabricating equipment, McAuliffe called upon all his stored-up powers as a mechanic, a welder and a contractor, a joiner of things to make something, most of it secondhand and all of it on the cheap. He even fabricated an apartment above the brewery, shower and stove included.

When he wasn’t brewing or bottling, he was doing his own distribution in Stern’s van and his own research at the University of California-Davis an hour away. It was there in the early 1970s that Michael Lewis devised the brewing concentration of the nation’s first four-year bachelor’s in fermentation science.

The university already had a long tradition of wine scholarship under faculty like Vernon Singleton and Maynard Amerine. Now, Lewis, a native Brit with a doctorate in microbiology and biochemistry, was crafting a curriculum that would transform the credentialing of brewers in America. (Before the UC-Davis program, if an American said he went to brewing school in the U.S., it invariably meant he had taken classes at the venerable Siebel Institute of Technology in Chicago.)

Lewis found McAuliffe “a vacuum cleaner of information,” comfortable for hours amid the UC-Davis brewing stacks. Lewis’ program would also be instrumental in advising McAuliffe on the yeast strains that would give New Albion’s porters, stouts, and pale ales their flavors.

The brewery quickly gained renown beyond the Bay Area, despite its limited distribution. No less a personage than Frank J. Prial, wine critic for The New York Times, visited for a column, though he took refuge in oenological similes. For instance: “Like true Champagne, New Albion’s final fermentation literally takes place in the bottle.”

Prial could be forgiven for not having the etymological chops to adequately describe traditionally made beer. The vocabulary had atrophied from lack of use, dwarfed by the oceans of verbosity spilt in service of lifting wine as the drink worthy of serious criticism.

Then along came a spectacled Englishman, with a goatee that could readily blossom into a beard and a plume of professorially unkempt hair, named Michael Jackson. Jackson discovered great beer during a 1969 side-trip into Belgium while on assignment in the neighboring Netherlands.

By 1976, he had authored a history of the English pub. The following year, however, he dropped what became a classic of 20th-century food writing: The World Guide to Beer. In a lively, yet fervid tone, Jackson dusted off and expanded a vocabulary for beer which influenced not only every beer critic who came afterward, but which inspired brewers to reimagine extant styles as well as resurrect ones near or past extinction.

Jackson’s book spent 14 pages on American beer (Maryland-sized Denmark, by comparison, got 10). “For all its great output, the United States has little more than 50 brewing companies, owning less than 100 breweries.” Still, he was hopeful, noting Anchor’s scrappiness in particular: “The smallest brewery in the United States has added a whole new dimension to American brewing.”

Indeed, Anchor throughout the 1970s had ticked off one milestone after another: first porter in modern times (1972); first modern American barley wine (1975); first modern American seasonal, a Christmas ale (1975); and what Fritz Maytag called Liberty Ale (1975), which, through its generous use of Cascade hops, became the prototype for today’s I.P.A.

Tom Acitelli

This story was adapted from the new book, The Audacity of Hops: The History of America’s Craft Beer Revolution by Tom Acitelli. He can be reached via email and on Twitter.

EXCELLENT article! Thanks so much.

Loved the 5 page start to the book. Where can I get it. Have been home brewing off & on for several years and have found this very informative on it’s history.

Thank you.

great article!