That Time Beer Saved American Fine Wine

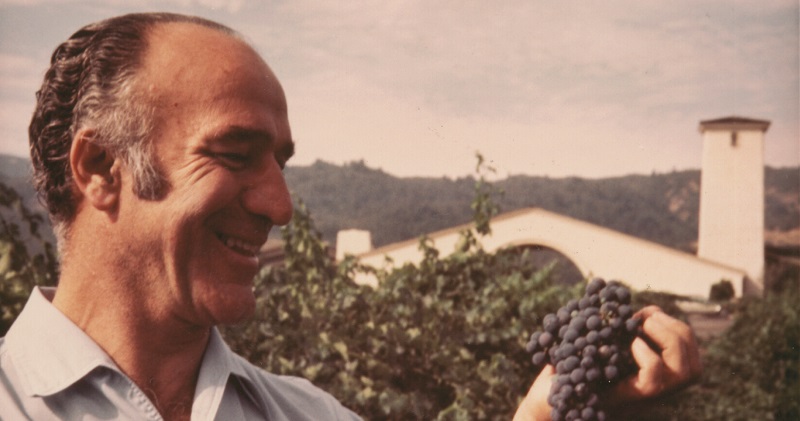

Rainier Brewing purchased a majority stake in Robert Mondavi Winery in 1968. (Photo courtesy Robert Mondavi Winery)

In early 1968, Robert Mondavi and his eponymous Napa Valley winery were in trouble.

Its production had grown steadily from its 1966 launch as the first significant new winery in America’s most ballyhooed winemaking region. Plus, Mondavi had gained all-important critical plaudits for his Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon in particular, which some said held their own against versions from the almighty French.

Still, though, the Robert Mondavi Winery was not making any money, mostly due to Mondavi’s free-spending habits (he couldn’t, for instance, have just any old oak barrels for aging—they had to be the best Europe had to offer). The winery’s failure would have meant a serious stunting of what was then an American fine wine movement toddling forth to do battle with the forces of domestic and international indifference.

Mondavi, scion of a Napa winemaking clan with whom he had split acrimoniously in 1965, was that young movement’s biggest star. A gregarious perfectionist, he was a kind of Fritz Maytag and Jim Koch rolled into one, selling not only his own brands but the very concept of American-made fine wine to the wider public.

If he couldn’t make a go of Cabernets, Chardonnays and other higher-end wines from European grape types, who could?

Then, beer stepped in to save him.

In early 1968, Ivan Shoch and Fred Holmes, two prominent Napa vineyard owners who had provided much of the capital for Mondavi’s launch, sold their majority stake to the Sick’s Rainier Brewing Co., a regional brewery out of Seattle (which Molson Breweries out of Canada controlled and which came to be better known simply as Rainier Brewing). Shoch and Holmes were, simply put, skittish about Mondavi’s spending and wanted to get out before, they believed, the bottom fell out.

As for Rainier, it wanted in on an industry related to brewing, one that a few giants did not almost completely dominate. Like a lot of regionals nationwide, Rainier had seen the beer marketplace shrink considerably since World War II, as Anheuser-Busch, Miller and a handful of others gobbled up, or froze out, smaller competitors. American fine wine did not yet have such giant firms.

Also, Rainier had $12.5 million in cash to play with as 1968 started. According to Mondavi biographer Julia Flynn Siler, Rainier had just sold its Seattle Rainiers minor-league baseball team for said sum. The brewery then went shopping in California wine country and found Mondavi.

Rainier allowed Mondavi to retain management control of his winery and did its best to rein in the vintner’s free-spending habits. The brewery, however, set the winery’s production benchmarks, including ramping it up to some 200,000 cases annually, a staggeringly ambitious number for fine wine in those early days, especially for an operation so young.

Mondavi the man was only too happy to oblige. Flush with cash, he did ramp up production and increase sales; and, while the winery would flirt with financial troubles for decades to come, it and its namesake became the most ubiquitous entities in American fine wine. It’s safe to say: No Robert Mondavi, no American fine wine as we understand it today.

And what of Rainier, unwitting savior of so much of American fine wine? In early 1977, the G. Heileman Brewing Co. out of Wisconsin acquired Rainier Brewing from Molson and other owners for about $7.9 million. Mondavi, who died in 2008, then bought out the Rainier shares and took full control of his winery just as it started to grow by leaps and bounds. Current owner Constellation Brands acquired it in 2004 as part of a $1.3 billion deal.

Rainier would stagger on through other ownership changes, its Seattle operations closing in 1999. Current owner Pabst recently resurrected the brand.

Read more Acitelli on History posts.

Tom Acitelli is the author of The Audacity of Hops: The History of America’s Craft Beer Revolution. His new book is a history of American fine wine called American Wine: A Coming-of-Age Story. Reach him on Twitter @tomacitelli.

Leave a Reply