How did you become involved with the Lhasa Beer project in Tibet?

When I was at Portland Brewing, one of the things we offered was consulting for other breweries. The Lhasa people came to me and said they were interested in brewing a beer in Tibet. I liked what they had to say. That was within a month or two of Pyramid buying Portland, so, when it was time to go to Tibet, I was no longer employed at Portland Brewing Co. and I went as Kornhauser Freelance Consultancy—KFC.

I flew to Tibet, looked over the operation there, and saw what they were capable of. This is a brewery that was built, I’m guessing, 15 years ago, so it’s not that old. The equipment was pretty good. To give you an idea of the quality, I did the initial work on this in August, 2004, and by January or February, Calsberg had come in and bought 51 percent of the brewery. And Carlsberg doesn’t play around with crap.

We looked for a kind of beer that would be quite drinkable, but would still have some twists of its own that would make it stand out from the crowd. There’s a unique hull-less barley indigenous to Tibet, and they malt it. We tried it, and the flavor was quite good, slightly different. So we’re using 30 percent of the hull-less Tibetan barley and 70 percent Australian malted barley.

There’s a lot of research going on, especially in Canada right now, on developing hull-less barleys, because you get a lot more bang for your buck—you aren’t paying for excess weight that doesn’t give you any extract. There also are malt mills in German—more there than elsewhere—that divide the husk from the barley kernels, so you just mash the kernels, and add the husks separately to the lauter tun, so you don’t get the tannin flavors from the husk. It’s one of those German overkill things. If there’s a simple way to make beer, the Germans can add three steps, to make it a little more complicated.

I thought the hulls were useful to a brewer?

Yes, they form a filter bed for lautering, but you don’t need 100 percent. Obviously, German wheat beers are 55 percent malted wheat, and that has no husk.

The other significant point about Lhasa Beer is that we’re using a tremendous amount of Saaz hops. We couldn’t dry hop there, which is what I wanted to do, so we went to the next best thing, which is the whirlpool tank. We’re using Czech Saaz hops and it has a very, very nice aroma. I tried to make it in the style of a European lager—good-selling beers—but somewhat more distinctive.

And it’s got a great story, with the proceeds going for Tibetan development efforts. Who started this venture: beer people or non-profit people?

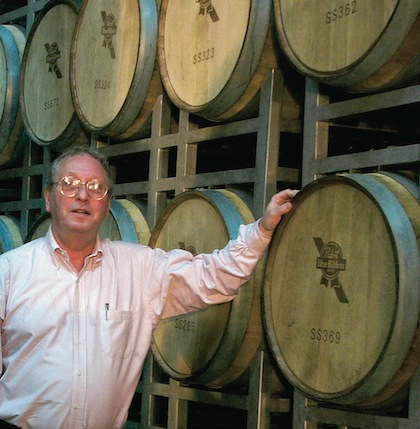

Both. It was a combination of a guy with an interest in Tibet, and a guy that knew a lot about beer. George Witz is the CEO and he’s our beer guy.

Tibet was completely eye-opening. The Tibetan people are not Chinese, they’re their own ethnic group. I’ve never seen a more religious group of people in my life. People walking down the street and prostrating themselves on their way to the temple. Tibetans are so kind and cheerful—they’re just the nicest people in the world. It is a kind of mystical, magical place.

Is the beer in Lhasa brewed for export?

It’s entirely for export. They have a brand called Lhasa Beer in Tibet, but that is a Carlsberg recipe, and it’s their license for China and Tibet. We hold the license for the United States and it is our own recipe—it’s a completely separate beer. The beers in China are for the Chinese market, and the beer in Hawaii is for the Hawaiian market.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Rhode Island, and I believe I am the only native Rhode Islander who lives outside of the state and is not in the witness protection program.

As a kid, we used to drive past the Narragansett Brewery, and those big old Gothic-looking breweries built in the 1890s. They made the beer that my father drank. From the time I was in grade school, I thought that would be kind of a neat place to work.

You’ve worked at every level in the beer industry. What’s your brewing history?

I started in the union at Huber Brewing Co. in Monroe, WI, in packaging. Then I sent myself to the USDA course in Brewing and Malting Science in Madison, back when nobody did that—mostly it was only big guys.

At that course, I met the then-head brewer at Anchor. My goal was to go to Heriot Watt in Scotland. But Anchor offered me a job and, since I had no money, I thought it was better to have someone pay me to learn how to make beer than to pay somebody else to teach me to make beer.

So I went to Anchor. I was there for a total of 18 years, but in the middle I took a one-year leave of absence and moved to Kyoto to study Japanese. Then I was offered the brewmaster job at G. Heileman in Milwaukee—they were reopening the Blatz plant, which had been closed for five years, so I was brought in to recommission it and be the brewmaster there.

I did all the R and D brews for corporate Heileman, and we did some contact brewing as well. Then, as Heileman was having their going-out-of-business sale, they sold the plant and me to Miller. Miller decided to make it into Leinenkugel Brewery number two. I formulated the first Leinenkugel brews there.

Since I knew Heileman was going to sell us, I had done a little fishing, and I actually had three other offers on the table, and one of them was Portland Brewing Co. in Portland, OR. So, off I went to Portland, and I was there for two years. I enjoyed it, but then Pabst offered me the job of brewmaster for Mainland China and I signed a two-year contract with Pabst.

Two years in China was enough and I came back to Portland for four years until Pyramid bought us. Portland had been contracting our canned beer at August Schell in New Ulm, and when it was apparent Pyramid was not going to keep me on, August Schell offered me the brewmaster job in New Ulm. About a year later, Pabst offered me the job back in China. I really liked living in Asia and so I went back to China for a year and a half, which, again, was about all I could take of living in Mainland China.

I love living in Japan, and I like Hong Kong, but the Mainland can be a little wearing at times. I worked out a deal with Pabst where I work every other month in China and in between…well, in between, I mostly don’t work. And I kind of like that.

I was commuting between the United States and Asia—I went to Asia eight times in 2007 and 2008. I was getting a little tired of that, so I relocated to Japan.

Our U.S. brewmaster for Pabst, Bob Newman, lives in Lehigh Valley, PA. But even though he is physically closer to Hawaii than I am in Kyoto, I can get there a lot quicker on a direct flight out of Osaka into Honolulu. He’s got to go Allentown, Philadelphia, Chicago…you know. So Pabst geographers have decreed that Hawaii is part of Asia.