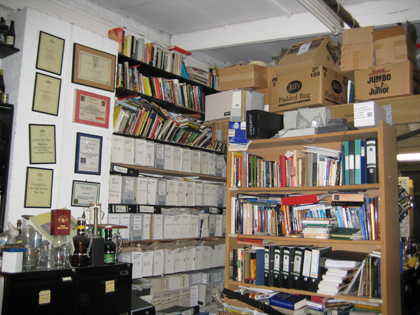

A view of beer writer Michael Jackson's office, the contents of which are now at a library in the United Kingdom. Photo courtesy of Oxford Brookes University.

The world’s best-known beer writer did not claim to get everything right at first.

“Obviously, I’m learning all the time, and revising my ideas. Nor did I start with the assumption that I knew better than anyone else,” Michael Jackson wrote to American beer importer Charles Finkel in 1981. “My initial contribution was not knowledge but a willingness to research.”

Jackson and Finkel were near the beginning of a friendship and business relationship that would last until the Englishman Jackson died in 2007. Finkel once said finding Jackson’s World Guide to Beer in 1978 “was to me like a heathen discovering the Bible,” and it was an essential reference in building the portfolio for his company, Merchant du Vin. Finkel had recently visited the author in London, and that the two were at ease with each other was obvious. Jackson suggested Finkel must have had a good time, because there was part of the evening the American apparently did not remember.

Jackson corresponded with total candor. “There is, in fact, no limit to the egomaniac self images I can conjure up, and will do, as raw images for anything you care to put together in Alephenalia [a newsletter Finkel created for Merchant du Vin],” he wrote. “Let me put it in another, mock-modest way: here are some of the aspects of my work in which I take pride.”

In the paragraphs that followed, Jackson did indeed forgo modesty, but more extraordinary in retrospect is how accurately he forecast, in 1981 and well before he became known as The Beer Hunter, a good portion of what he would be remembered for:— being the first writer to attempt an international study of beer styles, championing beer at the table, and using a “literate” vocabulary in his beer writing. Perhaps that vision explains why much of what he wrote before the current generation of beer drinkers was even born remains relevant today.

The Michael Jackson Collection

The typed carbon copy of what Jackson wrote to Finkel is filed along with more letters, promotional material and other documents related to Merchant du Vin inside a folder labeled MJ/4/14/211 in an archival box in the special collections room at the Oxford Brookes University library. In May of 2008, nine months after Jackson died, Don Marshall at Oxford Brookes supervised a crew that moved almost the entire contents of Jackson’s office in London to Oxford.

They packed up 83 linear feet of books (1,500 from his personal library and 300 copies of his own books, often with versions in multiple languages), the contents of 29 filing cabinets and 26 linear feet of archival material. The movers left behind only considerable quantities of beer and whisky, as well as most of the glassware.

Included among the objects moved were several pairs of Jackson’s glasses, Beer Hunter business cards, Christmas cards and a tattered copy of The Penguin Dictionary of Modern Quotations. Cut-up Post-it notes protrude from the top, acting as tabs, labeled with page and item numbers plus key words like beer, drink or porter. The last marks a quotation from J.P Donleavy, who wrote The Ginger Man.

It reads: “When I die, I want to decompose in a barrel of porter and have it served in all the pubs in Dublin. I wonder would they know it was me?”

The Beer Hunter’s place in history, as the world’s most prominent writer about whisky as well as about beer, was secured long before Jackson died. By donating all that he had accumulated, the executors of his estate, Paddy Gunningham and Sam Hopkins, assured the massive amount of information he collected would remain available to future historians.

What a great read about a legend of a man. Sometimes I almost cry knowing that I will never have the chance to meet Mr. M. Jackson. But then I remember all that he has given the culture of beer and I know I can hear him there.

“When I die, I want to decompose in a barrel of porter and have it served in all the pubs in Dublin. I wonder would they know it was me?”

Oh yes.