The first problem with butchering pigs is transportation—that is, assuming you don’t live on an actual pig farm, which, admittedly, would be nice.

Beer and meat were made for each other—arguably the two most important food sources in human history. And that’s where I come in.

A 4 x 8 U-Haul trailer, filled with plenty of hay, is a convenient way to take old Wilbur on his last ride. But getting Wilbur into the trailer creates a quandary. Pigs are not only tasty: they’re smart. And a cornered hog will do just about anything to avoid getting into the trailer, like dig a huge hole beneath the ramp, squeeze out from under the other side of your truck and then force you to chase it around the pen. Mr. Houghton, a Massachusetts farmer from whom I used to buy my pigs, found this incredibly entertaining.

I’d also suggest you don’t tell the U-Haul guy what you’re doing with his trailer, which would be sticking a 200-pound porker in it to take the hog from the farm to the slaughterhouse—unless you want to do the dirty work yourself—and then, with the pig cleaned and sawed in half snout to tail, from the slaughterhouse to your backyard. It helps if you keep the kidneys, too. Because then you can tell the age-old butcher’s joke:

“How do you cook the kidneys?”

“You boil the piss out of ’em.”

And, just a friendly FYI here, people will look at you funny when you walk across the donut shop parking lot with a bagful of crullers while said trailer is pitching from side to side, like a packet ship of pork in high, heavy seas.

But if you can handle the public scrutiny, a U-Haul is the way to go—and if you’re the type of person who prefers to spend an entire autumn weekend making your own pork chops rather than, like, buying them at the market, public scrutiny, shame or even ridicule probably have little effect on you.

Of course, you could always buy the donuts before picking up the pig. But live and learn.

Try This at Home: We’re Not Professionals, Either

The other problem with butchering pigs—perhaps the bigger problem—is figuring out which beer you’re going to drink that day, and on all the succulent days to follow, after you’ve turned Wilbur into thick pork chops, tender grilled loins, nutmeg-and-sage flavored breakfast sausage that fill your home with the spicy, intoxicating aromas of autumn and winter, and the smokiest, saltiest, most savory and most amazing hams you’ve ever had.

Beer and meat were made for each other—arguably the two most important food sources in human history. And that’s where I come in. I’m a semi-pro beer drinker, part-time pig butcher and full-time meat lover. Pairing suds with sausage is more than a hobby. It’s a tradition in my family, one that unfolds each year the way normal families might rent a summer beach house and grill hamburgers and hotdogs.

It’s also a tradition that connects us to an era when winter sustenance didn’t come in a shrink-wrapped package at the Mega-Mart, but from the work of your hands at harvest time, once the weather was cool enough to safely process meat outdoors.

Most beer lovers today, especially home brewers, appreciate the fact that it was only a couple centuries ago that beer was something you probably made at home, rather than purchased elsewhere.

The evolution of meat into a packaged consumer good is even more recent. If you’re middle-aged today, you’re among the first generations in history that grew up purchasing packaged chicken parts, for example, rather than whole chickens that were carved up at home. And as recently as the World War II era, when more than 40 percent of the U.S. population still lived in rural areas, Americans were as likely to butcher their own pigs as they were to purchase packaged pork.

So we make our own hams and bacons for many of the same reasons home brewers make their own beer: it’s more authentic, it’s more rustic, it’s more innately humane than buying beer or sausage made in stainless steel tanks at a modern factory.

And for my beer-and-meat loving family, our pig-butchering tradition has another appeal: we can trace its origins to the famous brewing town of Bamberg, Germany.

Bavaria’s Other Specialty

My father-in-law, Ray McConnell, was a young dentist and an officer in the U.S. Army in the late 1960s. While the Vietnam War raged, he landed a plum assignment at the American base in Bamberg—the same Bamberg famed for its gorgeous 1,000-year-old cathedral, for its timbered town hall hanging precariously from a bridge over the Regnitz River, and, of course, for its spectacular Franconian lagers, especially smoky rauchbier and dense, unfiltered kellerbier.

Bob Barker couldn’t have given away a more perfect prize: a four-year, nearly-all-expenses-paid trip to the historic heart of Bavarian man-town.

In addition to world-famous suds, the area around Bamberg, like most of Bavaria, has other culinary specialties that get decidedly less attention from beer lovers, but are just as deserving: an amazing variety of savory local meats you’ll rarely find anywhere else. There’s weissewurst, the Bavarian breakfast sausage speckled with onion and parsley; a smoke-cured beer-friendly beef snack called zwetschgenbaum; thin, dried hunter’s sausage called landjaeger, the Bavarian equivalent of beef jerky; and lebekase, a succulent pork and veal meatloaf, to name just a few. If anything in the world tastes better together than Bavarian beer and sausage, the gods of gastronomy have yet to share it with me.

These local specialties are served in the gasthofs of Bavaria, often sliced thin and placed on slabs of tree trunk turned into serving platters, or they hang tantalizingly in butcher-shop windows, the carnivore’s equivalent of the glass-walled brothels of Antwerp or Amsterdam, with naked flesh begging for attention.

Ray and his army buddies, often with families in tow, spent their free time touring the countless breweries and bierstubes in and around Bamberg, while feasting on the local delicacies. He would often bring my future wife, Lee, then just 5 years old, to the metzgerei (butcher shop) to translate and barter with the proprietors. She learned English at home and German everywhere else. Like most children, she soaked up languages more quickly than her parents.

Ray’s dental assistant at the base was a Bavarian girl whose family owned a farm where they raised pigs and made sausage. A do-it-yourselfer by nature, he’d visit the farm to learn tips of the trade from Franconian sausage-makers.

Back Home, with Something Missing

When they returned to the States in the early 1970s, Ray and his wife, Marilynn, bought a large spread in rural Rhode Island to raise their four children. They also raised cows, chickens, pigs and horses, filled their own root cellar with homemade pickles and sauerkraut, grew grapes and hops, and shot the occasional turkey and deer that ventured into the yard.

But something was missing from this idyllic little corner of New England: the bier und wurst of Germany. So Ray taught himself how to turn the family’s pigs and cows into everything from New England-style breakfast sausage to Old World-style headcheese. He was aided by a guide he ordered from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (Farmer’s Bulletin No. 2265: Pork Slaughtering, Cutting, Preserving and Cooking on the Farm…great read), the tips he learned from the farmers back in Bavaria and a very patient wife (a trait passed on to their daughter, Lee).

Beer worthy of his creations remained a problem. So Ray opened his own brewery, Emerald Isle Brew Works, in the 1990s. Instead of German-style lagers, he made something more typical of old New England: frothy, unfiltered, cask-conditioned ales that he sold to pubs around Rhode Island and Massachusetts, but more often than not shared with friends and family.

Meanwhile…

About the time my future in-laws were brewing beer and making homemade pickles and sausage, my family and friends were firmly entrenched in our own meat- and beer-filled tradition, one with a distinct American flavor: hosting a big outdoor tailgate breakfast each Thanksgiving morning.

The party precedes the local high school football games, which kick off at 10 a.m. and are as much a part of Thanksgiving tradition in New England as turkey and cranberries. If it once walked, swam, flew, jumped or crawled, we’d cook it and eat it. Alligator, venison, rabbits, ostrich and moose all made appearances at the Pigskin Gala, as we call it. Breakfast was always washed down with thick, bitter, unfiltered pints of India pale ale (and the occasional nip of schnapps) that we’d pick up from a local Boston brewery and tap, amid great Pomp and Circumstance, at the rooster-cackling hour of 6 a.m.

In most cases, sharing tales of an event that basically consisted of eating exotic animals and drinking beer before sunrise on a frosty November morning is not the way to impress a young woman.

But when I told Lee, my future wife, of my family’s plans for Thanksgiving, it all seemed so, well, normal to her. Her German had disappeared over the years. But her love of wurst, cultivated bartering in the butcher shops of Bavaria, had not.

A Family Tradition

A pair of disparate family traditions soon evolved into a rustic celebration right out of Colonial America or Old World Bavaria.

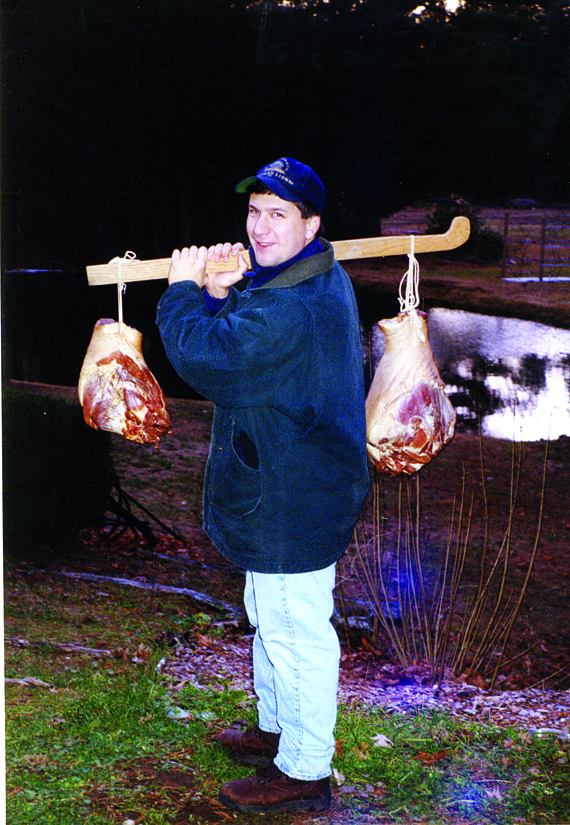

The tradition today begins in mid-autumn, amid the famously colorful blaze of New England’s orange oaks, yellow elms and flaming-red maples. With little more than a meat saw and a few sharp knives, we butcher the season’s pigs outdoors, with German fest beers, Paulaner and Hacker-Pshorr most notably, or the occasional Mahr’s Brau kellerbier, lubricating the affair. Chops, loins and shoulders are wrapped fresh in freezer paper and stored away. Hams, hocks and pork bellies are stuck in huge crocks of salt-and-brown-sugar brine. Loose meat and pork fat is ground into sausage, flavored with nutmeg and fresh sage cut from the herb garden. We always fry up a few right away—just to test this year’s batch, of course.

The tradition continues on a chilly November weekend, with the heartiest last leaves clinging to grey branches. We huddle around the smokehouse for three days, feeding fresh-cut New England maple logs into the firepit, turning the briny slabs of pork belly and pig butt that hang from wooden beams into reddish-brown hanks of bacon and ham, and pouring clean, smoky brown pints of Schlenkerla or Spezial rauchbier into steins brought from these famous Bamberger beer halls to lend an authentically Bavarian flavor to the occasion.

The tradition reaches its climax throughout the late autumn and winter—the Pigskin High Holidays, I call it, for the neatly wrapped package of football and family festivities that define the season. First, there’s the beer-soaked breakfast of the Pigskin Gala on Thanksgiving morning. Once, we’d eat anything. But today the event is flavored almost exclusively by homemade sausages and bacons and by traditional, unfiltered New England-brewed ale poured from the wooden tap of a firkin and spiced with a bag of Boston-grown hops picked from my backyard each summer, dried and stuffed into the barrel.

The Pilgrims ate venison at the first Thanksgiving, just 30 miles south of the Pigskin Gala, so we do the same. On ham-smoking weekend, we grind fresh rich-red venison, add thick beef fat, spice the meat with white pepper, ginger, nutmeg and sage, stuff the flavored mixture into lamb intestines and smoke them for several hours to a deep, dark brown. The smoky venison links are fried in a cast-iron skillet on Thanksgiving and then throughout the winter, often alongside our nutmeg-flavored pork sausage, creating an aromatic meritage you’ll simply never experience with bland, store-bought meat.

Forward to Christmas and New Year’s Eve, when we pound mugs of sticky, bitter golden-cranberry-hued Sierra Nevada Celebration Ale while ripping shreds of meat from a big ham that, as it bakes, yields a black-and-brown tar-like sludge of salt brine and pork fat that’s so intoxicatingly flavorful it buckles your knees.

The tradition concludes on Easter, when the smoky aroma of the year’s lone remaining ham fills the house for the last time until autumn, bocks and spring ales washing down the final remnants of savory pork for the season.

But pork, like hope, springs eternal: somewhere in New England this March, there will be a new little piglet named Wilbur fattening up for the ride in October.