In April 2010, as the world’s airlines were grounded by volcanic ash, all the signs indicated that the Campaign for Real Ale’s annual conference would be poorly attended. It was due to take place on the Isle of Man, halfway between Britain and Ireland in the Irish Sea. The island’s capital, Douglas, is a short hop from British airports but no planes were taking off or landing.

Founded in 1971, the grassroots movement that saved cask ale is attracting a new generation.

When the doors of the conference hall opened, I expected to see a thin trickle of CAMRA members. But they came rushing in, several hundred of them. They had come by train and ferry. Such is their legendary enthusiasm for beer, there’s no doubt that some would have rowed or even swum to get to Douglas.

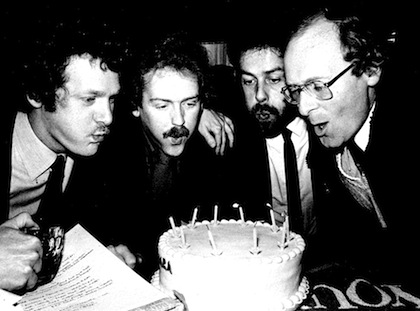

CAMRA's four founders—Jim Makin, Bill Mellor, Michael Hardman and Graham Lees—celebrating CAMRA's 10th anniversary.

This year, the conference will be based in Sheffield in Yorkshire, more easily accessible by train or car. And there will be much to celebrate, for CAMRA, founded in 1971, is 40 years old. It started with four members, had grown rapidly to 29,000 when I joined in 1976 and today boasts a membership of 125,000. It’s a power in the land. Its officials are routinely called in by both British and European parliaments to discuss such matters as levels of excise duty and the imbalance of buying and selling power between supermarkets and pubs. For example, CAMRA’s chief executive Mike Benner addressed members of the European parliament in Brussels in December.

But equally important, it’s CAMRA’s beer festivals—at least 12 a month, culminating in the Great British in London every August—allied to the rise of craft brewers that have put the seal on the campaign’s success and vitality over the past 40 years. It’s a uniquely British institution. The image of the Brits—introverted, victims of the stiff upper lip—could not be more misplaced. Go to any major soccer or cricket match, and you’ll witness a different side to the island race: passionate and committed.

And it was that passion and commitment to traditional British beer that fuelled the rise and influence of the campaign. It will come as a shock to most CAMRA members to learn that their organisation is rooted in Britain’s imperial past. But it was the Victorians’ determination to remain loyal to ale and, in particular, its cask-conditioned version that led to the rise of this remarkable consumer revolt a century later.

In The Beginning

In the 19th century, a small island had painted half the globe red. While mainland European countries remained largely rural and agricultural, Britain was a powerhouse of industry and innovation. It exported its products throughout the world, beer among them. The holds of sailing ships were weighed down with great oak casks of British ale that eventually slaked thirsts in India, Australia, the Caribbean and North America.

William Bass started a tiny brewery on a patch of land in Burton-on-Trent in the late 18th century and a century later his sons had turned the company into the biggest brewery in the world, making more than one million barrels a year. Thanks to new technology, British brewers had developed a style of beer—pale ale—that bewitched the world. Great brewers such as Gabriel Sedlmayr in Munich and Anton Dreher in Vienna came to Britain, and Burton in particular, to see how pale ale was produced. They returned home, determined to make their dark lagers paler in colour. The first truly golden lager from Pilsen was made possible by a malt kiln imported from England.

British brewers, pumped up with imperial pride, saw no need to switch to lagering—cold fermentation and maturation—even when they rapidly lost most of their overseas trade to the new type of European beer. Brewers in Britain still had a large internal market to satisfy and they could now move beer around with comparative ease thanks to the rise of the new railroad system.

The question is obvious: if British brewing was so successful, why was it necessary to launch a consumer movement in the 1970s to protect its major beer style? The answer lies in Canada. In the 1960s, a Canadian called Eddie Taylor owned the rights to a lager beer called Carling Black Label. He was successful in his own country but Canada has a small population and he thought greater success could come in Britain, one of the biggest beer-drinking countries in the world, where the natives more or less spoke the same language as he did.

In a whirlwind few years, Taylor changed British brewing beyond all recognition. To produce Carling he needed breweries and pubs—at the time 80 percent of beer in Britain was consumed on draft in pubs. Within a few years, he had bought and merged a number of breweries in the north of England to form Northern United Breweries. He added the famous London brewer Charrington to the pot, followed by Tennents in Glasgow. His greatest coup was to talk mighty Bass into joining a group he renamed Bass Charrington. By the end of the 1960s, Taylor controlled 20 percent of the brewing industry, owned 10,000 pubs and enjoyed an annual turnover of £900 million.

And he’d frightened the life out of other big brewers, who huddled together for comfort. A series of mergers and takeovers produced what were dubbed the Big Six: national brewing groups that included such famous and historic names as Courage, Tetley, Truman, Watneys and Whitbread. The emergence of the Big Six coincided with the development of a national network of new super highways—Britain’s motorways. The national brewers could move beer around at speed but they wanted a new type of beer that was not perishable like cask ale and had a longer shelf life. For all his bravura, Eddie Taylor had not achieved overnight success with Carling lager. The Brits were doggedly determined to remain true to ale. The response of the Big Six was to fashion a new type of ale called keg beer that was filtered, pasteurized and artificially carbonated.