The children are nestled all snug in their bed,

Santa’s outside, he’s full of dread.

The old elf’s been working hard all night,

Inside awaiting, it’s the same old blight.

Milk and cookies, usually they’re stale.

Won’t someone leave him a righteous pale ale?

Drying out Santa, however, has always been a losing cause thanks to the eternal connection between Christmas and beer.

Listen kids, contrary to the tales Mom and Dad told you, Father Christmas did not get that round belly and red nose from sucking down glasses of skim. Not to destroy your innocent visions of sugar plums and candy canes, but when it comes to treats on a long winter’s night, if it’s all the same to you, Santa Claus would rather have a beer.

Or, as they say up at the North Pole, “Ho, ho, hic!”

Sacrilege, you say? The very symbol of childhood innocence guzzling alcohol? What’s next, Winnie the Pooh doing Jello shots?

In fact, from the very beginning, Santa Claus was a man of drink.

His alter ego, you might recall from Catechism, is Nicholas of Myra, a 4th-century Turkish do-gooder who was venerated as St. Nicholas, the ancient patron of an assortment of riff-raff, including prostitutes, lawyers and, yes, brewers.

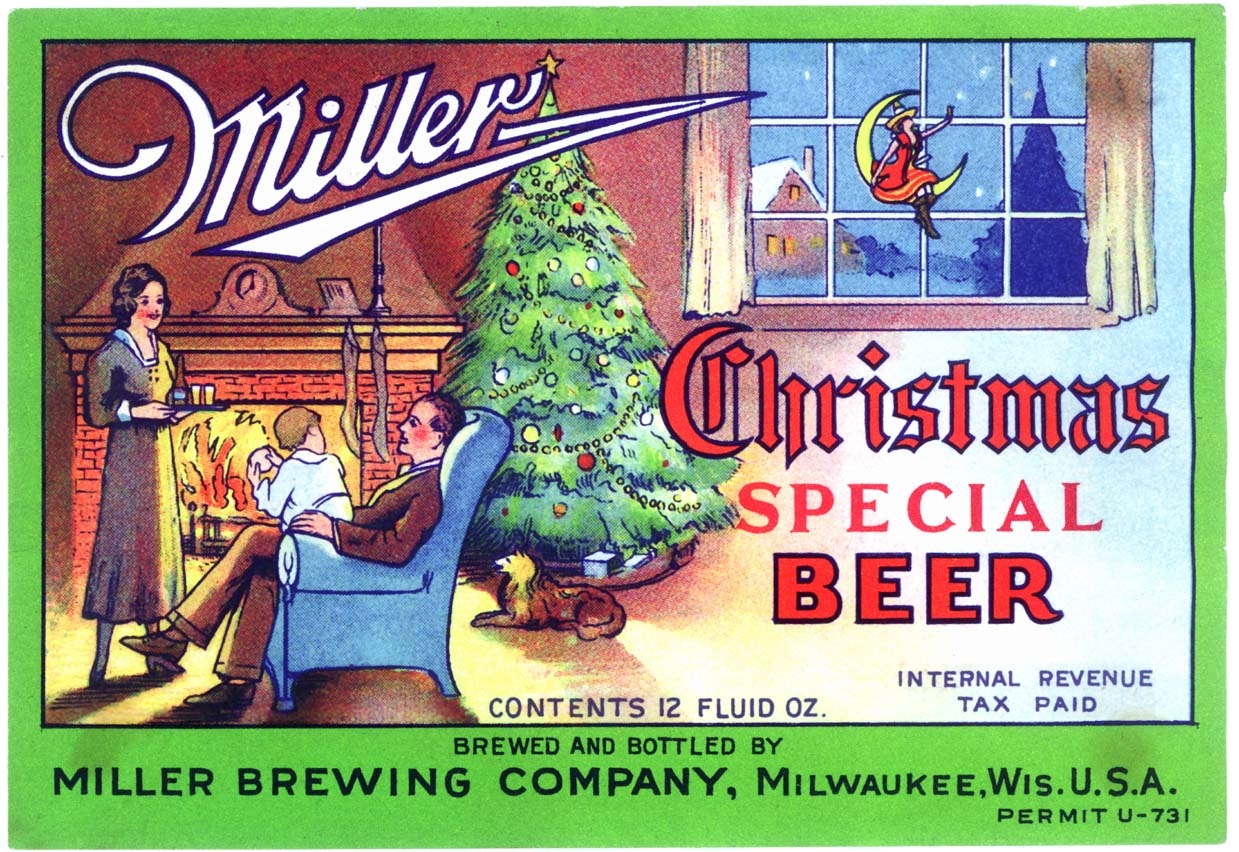

St. Nick eventually morphed into Santa Claus, a fat, jolly, pipe-smoking elf. Shortly after Clement Moore wrote “A Visit from St. Nicholas” in 1823, advertisers began using him to shill everything, from shoes to cigars to, yes, suds.

In 1900, one magazine advertisement proclaimed, “Wherever children look for Santa Claus, Schlitz beer is known as the standard.” A few years after that, a full-color Life Magazine ad portrayed a soused Santa reading kiddies’ letters while sucking down a bottle of whiskey.

And so it went, from Augie Busch’s Clydesdales pulling a sleighful of Budweiser to Spuds MacKenzie dressed in a red Santa suit.

Not surprisingly, nannies and prohibitionists condemned those who suggested that Santa (a legal adult) had a taste for intoxicants.

In the 1930s, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union campaigned to outlaw the use of his red-suited image in booze ads. One leader testified before Congress that “Santa Claus, patron saint of children during the holiday season, was pictured loaded down with beer bottles, drinking cocktails, serving as bartender…”

Some 30 states ultimately enacted laws banning Santa from beer ads. It was those rules that the importers of Santa’s Butt Winter Porter and Very Bad Elf Special Reserve Ale ran into a couple of years ago, when authorities in New England sought to ban sales of the bottles. “Undignified and improper” was the way Maine state liquor officials described the cartoon of Santa dangling precariously over an open fire on the label of Warm Welcome Nut Browned Ale.

The Beers for the Solstice

Drying out Santa, however, has always been a losing cause thanks to the eternal connection between Christmas and beer. The December holiday began well before the birth the Christ, with ancient drinking celebrations to mark the winter solstice. To early man, the sun was God, and the day when it sat lowest in the sky signaled the start of a new cycle of life. The harvest was complete, the cold months ahead. The ale was plentiful, the festivals began.

The Egyptians, the Mesopotamians, the Greeks, the Scandinavians—they all bowed to the winter solstice. The pagans marked the event with their best food and strongest drink during Saturnalia, in honor of the god of harvest, Saturn, from December 17 to 25.

In the 4th century, as the western world became Christian, Pope Julius I would name the last day of the fest, December 25th, as official date of Christ’s birth. Many historians believe the date was selected so that pagans, forced to bow to a new religion, could keep their annual festival.

The winter party never stopped. By the Middle Ages, Christmas would be celebrated by Trappist monks raising goblets of their finest, strongest beer. Abstain from alcohol on this holy day? In the 12th century, no less than Francis of Assisi scoffed at the idea.

In Norway, farmers were required to brew a special Christmas beer, known as juleøl. Under law, the batch had to be made with as much grain as the combined weight of the farmer and his wife, or else they risked expulsion from their property.

The tradition of special drink for this special day only grew. In the 1600s, singing revelers throughout Europe would march from door to door with cup in hand, in search of bowls filled with spiced ale—wassail. One popular 18th-century ditty opened:

Wisselton, wasselton, who lives here?

We’ve come to taste your Christmas beer.

The pious objected to the drunken traditions. In 1659, the stiff-collars who ran the Massachusetts Bay Colony—complaining of Compotations, Interludes and Revellings—banned Christmas.

It wouldn’t last. Throughout the Revolution, American patriots would celebrate the holiday with “a right strong Christmas beer.” And in the next century, when Santa Claus evolved as the symbol of Christmas, he was frequently portrayed with a drink in hand.

Milk and cookies? Bah humbug! As Goebel Beer urged in 1910: “Drink deep of the brew that restores one’s faith in Santa Claus.”

Yes Virginia, Kringle needs a pop. Malt, yeast, water, and plenty of hops.

An IPA? It’s hard to choose? A dark stout? Too many brews.

Hurry now, I hear jingle bells. The question is clear as a glass of helles.

Take a moment, try to think: this holiday season, what would Santa drink?