The growing number of entries to sour beer categories

suggests that brewers are onto something new.

But the techniques they’re using, and the “bugs” they’re

welcoming into their beers, have a long history.Sour is the new bitter!” trumpets a newspaper column. Yikes, that sounds like a hard sell. So hostility has replaced resentment?

No, not really. We’re in the world of specialty beer, where sour and bitter can be positive things. The headline refers literally to two basic human tastes and the possibility that a new flavor may be gaining ground with beer lovers.

In recent years, craft brewers have reveled in pushing the bounds of bitterness, challenging their thirsty fans with beers heaped with hops. Starting with India pale ales and their more aggressive younger siblings, imperial IPAs, the trend then spread into other categories, with pilsners, porters and barley wines jostling for bitter supremacy.

(Photo courtesy of Port Brewing Co.)

But craft brewers are a restless bunch. Lately, a growing number have looked to another element to balance beer’s basic sweetness: instead of bitter-sweet, these beers lean towards sweet-sour. And although the term “sour beer” sounds off-putting at first, there are some exciting flavors awaiting the adventurous drinker. Sour beers faithfully preserve a centuries-old legacy. And, to the delight of modern drinkers, today’s brewers are shaping old styles and techniques to produce an array of new possibilities.

Sour—And More

As we learned through the bitter era, bitterness in beer is not one-dimensional. It can come from a number of sources and be expressed in an array of intensities. Most obviously, hops add bitterness. But the hop variety, the amount used and the timing of its addition, as well as its combination with other varieties, can take a beer from lightly floral to teeth-peelingly harsh. And hops are not the only source of bitterness: Roasted grains, malted and unmalted, can add a burnt-toast astringency to a beer even when the presence of hops is negligible.

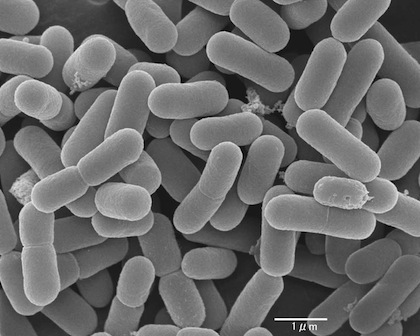

So it is with sourness. An assortment of bacteria can contribute sour tones to beer, with intensities that range from lightly tangy to puckering. Rogue yeast strains also contribute acidic notes, and all these organisms produce different effects depending on their succession in fermenting and aging beer. And fruits, spices and other unusual additions can contribute to a sour profile.

Lumping all these beers under the description “sour” runs the risk of emphasizing their most simplistic quality. Jeff Sparrow, the Chicago-based beer author of Wild Brews, originally titled his book Sour Beer. But as he explored the Belgian brewing traditions that have contributed so much to the topic, he changed his mind. “I always say that this beer isn’t sour—it’s wild. I say that because, if all a beer was, was sour, who’s going to like it? There’s so much more going on.”

That’s true, but “sour beer” is the term showing up in both headlines and competition categories, which makes “sour” hard to avoid as a leading descriptor.

But Sparrow is right, there is much more going on. In fact, there are three closely overlapping trends attracting attention in specialty brewing. Although all three can have a role in a single beer, they can also exist alone or in combination. It’s a useful exercise to tease them apart: You may discover you like one or two qualities, or you may embrace them all.

Sour Beer: Our tongues register sourness as one of the five basic tastes (sour, bitter, sweet, salty and umami). Taste buds can detect levels of acidity: basically, they measure the pH value. More sophisticated discrimination—does this taste tart? Is it lactic? Is it vinegary?—relies on the interaction of our senses of taste and smell.

The primary sources of acidity are the closely related bacteria Lactobacillus (the sour milk bacteria) and Pediococcus, which both produce lactic acid; and Acetobacter, the source of acetic acid, or vinegar. Lactic acid is a relatively simple flavor, with a sweet-sour quality; acetic acid is sharper. And both acids can interact with alcohol to form chemical compounds known as esters. When all these elements combine, they can produce great complexity in a beer.

Wild Yeast: Brewer’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was purified in the late 1800s, allowing brewers to exclude other yeasts they found undesirable. One particular genus of “wild yeast,” Brettanomyces (“Brett”) is considered a source of off-flavors in both beer and wine. Indeed, the common Brett descriptors—horse blanket, band-aid, barnyard, sweat—scarcely sound appetizing.

But fans of lambic, Belgium’s most ancient beer style, recognize these flavors and aromas as essential components of these complex beers. Other Belgian beer styles display lower but still important levels of Brett as part of their character. And now, a number of American craft brewers are infatuated with these wild yeasts whose presence once would have been considered an infection, and are learning to deploy them in their beers.

Brettanomyces also contributes some acidity to a beer, but that can be easily overwhelmed by other sources.

Wood or Barrel Aging: For centuries, brewers used wooden containers to ferment, age and store their beer. When an alternative presented itself, most brewers happily adopted materials that were easier to sanitize and more resistant to invasion by unwanted organisms.

But some brewing traditions clung to wood’s qualities. Wood is permeable to oxygen, which allows communities of organisms to live on and in its surface, where they contribute to beer character. If allowed to, Brettanomyces and other organisms will take up residence permanently in wooden barrels.

Wood has other qualities, too. Oak, the most common material for food-grade barrels, releases vanilla-like compounds into the barrel’s contents. Wine makers value different species and sources of oak for different wines, and distillers have learned to char the inside of a barrel to impart toasted and caramel notes to spirits. Brewers take advantage of both new and used barrels to give their beer added flavor.

Wood- or barrel-aging, then, can mean different things: It may be that the beer is affected by the flavors of the wood itself, or by previous liquids stored in the wood, or by microorganisms that colonize the barrel—or all three.