America is dotted with the corpses of old breweries. You might have passed them while driving through some forgotten inner-city neighborhood: brick-and-mortar behemoths, four to five stories high, sometimes with gaps in the wall where copper brewkettles and other objects of value were extracted.

The German immigrants who founded these companies intended to build buildings that would last hundreds of years and become their legacies.

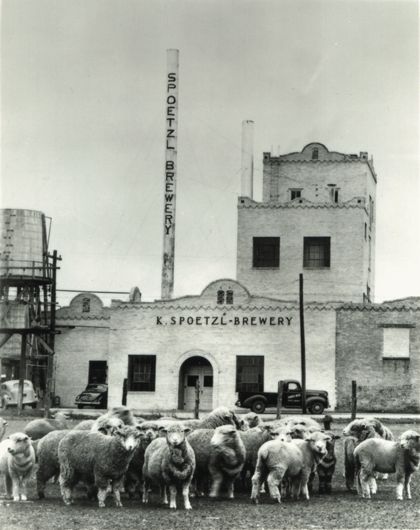

The original Spoetzl Brewery

In neighborhoods like Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhein, Philadelphia’s Brewerytown, Baltimore’s Brewers Hill and Boston’s Roxbury and Jamaica Plains, these early lager plants were once part of the city’s economic backbone. Some were almost self-sufficient communities, encompassing brewhouse, stockhouse, power plant, administrative offices, stable, bottling plant, and Bierstube, where thirsty workers could down a few on the house after a hard day’s shift.

The mass consolidation of mid-century drove most out of business. The buildings, according to Pennsylvania brewery historian Rich Wagner, became “white elephants”: too expensive to develop, too much trouble to tear down.

In time, the real estate beneath the brewery might become valuable enough, or the building become enough of a public nuisance, to summon the wrecker’s ball. Wagner, who along with his research partner Rich Dochter has been documenting brewing history and organizing brewery tours since 1980, has seen this happen too often. Last year, Schmidt’s of Philadelphia, a once-powerful regional capable of turning out over 3 million barrels a year, bit the dust. “It’s a vacant lot ready to become something else,” says Wagner. “There’s talk of building artists’ lofts.”

Sometimes, these old brewery complexes can be turned into showcases. The Jax brewery in New Orleans became an upscale shopping center. The Stegmaier plant in Wilkes-Barre, PA, one of the architectural gems of the Northeast, was saved from destruction by preservationists and breweriana collectors and now houses a post office distribution center and federal office space.

“If you can go into a place that used to be a brewery and make it a brewery again, that’s icing on the cake,” adds Wagner.

A few urban homesteaders have done just that.