From Bees to Beers: Exploring the Links Between Bees and Beers Brewed with Honey

Meredith Sutton bought Kevin Ryan a homebrew kit for Valentine’s Day in 2012.

Ryan bought her a top-bar beehive for Christmas in 2013.

The couple opened Service Brewing Co. in Savannah, Georgia, in 2014 with four hives in back. One-sixth of the beers they sell are made with honey, and wild yeast captured from cuttings of a honeycomb ferments some of their beers. “Having hives at the brewery has been fun for Kevin and I. You learn a lot from bees,” Sutton says.

Meredith Sutton and Kevin Ryan of Service Brewing Co. (Photo by Adam Kuehl)

Bees quite obviously are a significant part of their business, and elsewhere across the country bees surely deserve some of the credit for more beers made with honey showing up in drinkers’ glasses—not necessarily honey beers, but beers made with honey. Quite simply, connections between bees and beers include conversations about more than the honey they contribute.

American brewers used 25.4 million pounds of American honey in 2015. “We really don’t see it slowing down,” says Keith Seiz, a spokesman for the National Honey Board, which commissioned the honey-use survey. Anecdotal information already suggested under-the-radar growth. Representatives of the Honey Board, an industry-funded agriculture promotion group, took a booth at the Craft Brewers Conference for the first time in 2014. “About 20 percent of the brewers we talked to said they used honey. The next year it was 50 percent. Last year it was 80 percent,” Seiz says. “All of our producers say they are getting more calls from brewers than any other segment.”

Keith Seiz of the National Honey Board (Photo by Jonathan Galbreath)

The Honey Board organized a Honey Summit in 2014, inviting a handful of brewers across the country to gather in St. Louis for what has turned into an annual event where they discuss brewing with honey. “We started looking for resources and found there weren’t many,” he says. The board has since worked with Hugo Patino, formerly of Molson Coors, to assemble a “bible of brewing with honey.” A primer, it lays a foundation that brewers may build on by leaning backward perhaps 9,000 years or pushing deeper into the 21st century.

Beginning of Bees

Humans, honey and beer go way back, although not as far back as bees. Scientists don’t exactly agree on how long bees have been around and which of seven families of bees is the most primitive, but they likely evolved from wasps 130 million years ago. Bumblebees and honeybees emerged somewhat later. Eleven species of honeybees make up the genus Apis, with the Western honeybee (A. mellifera) the one most widely used for honey production. It is native to Western Europe and sub-Saharan Africa and was introduced in America in the 17th century, when Native Americans called it “the white man’s fly.”

Wilk Apiary keeps hives in multiple locations in New York. (Photo courtesy Wilk Apiary)

Rock paintings suggest that humans were collecting honey from wild bee colonies by 13,000 B.C. Efforts to domesticate bees using artificial hives began about 7,000 B.C., according to traces of beeswax found in broken pottery at archeological sites throughout the Middle East. It wasn’t until the 18th and 19th centuries A.D. that keepers developed hives they did not need to destroy while harvesting honey. They operated much like those used today. Virgil’s fourth book of Georgics had served as the basis for most beekeeping manuals for about 1,800 years before that, although it was a mixture of myth and useful information. For instance, it perpetuated the Greeks’ and Romans’ belief that bees sucked their young fully formed out of flowers.

However, centuries of folklore also illustrate the respect beekeepers have for their colonies. “Telling the bees” is an old custom widespread in Europe, one that was followed by early American settlers. Because the relationship between a keeper and his bees is believed to be so close, they must be told when he or she dies. They were told by members of the family, who would knock on the hive three times, saying, “The master is dead. The master is dead.”

Similar stories are part of the appeal of keeping bees. The Honey Board estimates there are between 115,000 and 125,000 beekeepers in the United States, most of them hobbyists with fewer than 25 hives. “I do it for the bees,” says Tom Wilk, who founded Wilk Apiary in 2012 and keeps hives in New York in seven locations in Queens and one on Long Island. “I wanted to learn more about them.” New York City legalized beekeeping in 2010 and now has almost 300 registered hives, according to the Department of Health.

Wilk sells most of the honey the bees produce, as well as some from other keepers, at local markets. “This isn’t really a business. It’s a weekend job that supports a hobby,” says Wilk, who is a sales manager at a large liquor distributor. A few breweries are regular customers, such as Big Alice Brewing and Transmitter Brewing in Queens. Wilk keeps three of his hives—he had 35 in 2016 and in March expected to tend to 30 to 40 this year—at Finback Brewery in Queens.

Brewing with Honey

Not long after Ryan and Sutton started dating, one of their regular walking routes took them past 17 beehives. One evening they met the keeper, and soon Sutton was there every Sunday, learning more about bees. She joined a bee club and found a bee teacher. Ryan used honey Sutton’s bees produced when he was homebrewing, but her bees wouldn’t be able to keep up with Service Brewing.

Service Brewing Co. (Photo by Adam Kuehl)

Ryan expects to brew 3,000 barrels of beer in 2017, about 500 of them made with honey. He’ll use about 4,000 pounds. They’ll buy those from Savannah Bee, a local company. “We’d need 70 hives,” says Sutton. “I don’t harvest too much honey, but do take a little to share with chefs and friends of the brewery,” she says. And she values what she learns from her bees, such as “that women should rule the world.” After laughing long and hard, she explains, “Really, they just make you think a lot. Reaching out to other beekeepers, trying to figure out what they are doing.”

Producing honey itself is relatively simple, but a colony is a complex society. A worker bee will visit between 50 and 100 flowers during a single flight, using her elongated tongue to access nectar deep within the flower, muscles in her mouth creating a vacuum with which to suck it out. She stores it in her honey stomach before returning to the hive. In total, members of a hive will fly more than 50,000 miles and visit 2 million flowers to produce 1 pound of honey.

After a worker bee returns to the hive, she regurgitates the honey into the mouth of a house bee. The house bee reduces the amount of moisture in the pollen by repeatedly regurgitating it to the tip of her tongue for faster evaporation. After her stomach is full of concentrated pollen, she will deposit it into a cell in the comb, where it will continue to dry until the water content has reached about 17 percent. Then house bees will cover the cell with wax.

A colony is made up of a single queen, who primarily lays eggs (2,000 a day); up to 80,000 sterile females, who are the worker bees and perform all the tasks associated with maintaining a hive; and fertile males called drones, who make up less than 1 percent of the population and exist to inseminate the queen. Workers live about six weeks during honey production season, first performing a variety of jobs as house bees, then literally working themselves to death as foragers.

A hive at the Honey Summit in 2016. (Photo courtesy Stan Hieronymus)

In 1927 Austrian ethologist Karl von Frisch described how scouts or returning foragers communicate the best food sources to others in the hive. He deconstructed both a round dance, for when there was nectar nearby, and a waggle dance, which provides directions to sources that might be up to 5 miles away. The complex exercise passes along a trove of information, even taking into account the movement of the sun, but it is the waggle—in which the bee shakes her abdomen—that makes is particularly memorable.

In the mid-1990s, the Vaux brewery in England brewed a beer it called Waggle Dance, made with 20 percent honey. The brand changed hands as various owners went out of business, and it is now in the hands of Charles Wells. It was at first labeled “The Original Honey Beer” and at the time beer authority Michael Jackson wrote, “Rather extravagant, that.” He pointed out that “honey has sporadically been used in beer through the ages,” which is about as simply as the history can be summarized.

The use of honey in something akin to beer could go back 9,000 years, but that history intertwines with mead and braggot, a mixture of honey and grain or of mead and grain. A few data points:

- Dogfish Head Craft Brewery made the first two beers in its Ancient Ales series—Midas Touch and Chateau Jiahu—with honey, basing the recipes on research by Dr. Patrick McGovern at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia. McGovern describes them in his book Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages. It’s less clear if the older beverage, Chateau Jiahu, from 9,000 years ago, would have included grain. However, McGovern writes with certainty about what he labeled “Phrygian grog,” because he identified residues found in the tomb of King Midas and dating to 2,700 years ago as barley, grapes, honey and saffron.

- Archaeological finds from the Neolithic to Bronze Age in Scotland suggest that a honey-and-grain drink was being consumed in Britain three to six millennia ago. Martyn Cornell adds, in Amber Gold & Black: The History of Britain’s Great Beers, that it would have been flavored with meadowsweet. He also reports that wheat-and-honey ales continued to be made into the Iron Age.

- Writing in Women in Anglo-Saxon England, Christine Fell suggests, “Since honey was the only form of sweetener available it is not improbable that the distinctions between honey-based alcohol (medu/mjoor) and honey-sweetened alcohol (beor/bjorr) might become blurred.”

- In Origin and History of Beer and Brewing, John Arnold maintains that references suggesting mead and honey beer were the same are wrong. He points to a nunnery at Herford in Westphalia that was granted the right in 1025 to make mead, beer prepared with honey and beer prepared without honey.

A Taste of Place

Braggots neatly link the past and present as well as bees and beer on Rogue Ales’ farm south of Independence, Oregon. Bees pollinate dozens of crops, including the marionberries that end up in Marionberry Braggot along with honey the bees produce. Nationwide bees pollinate 130 crops, and worldwide bees pollinate 400 crops. In fact, the value of these crops easily exceeds the value of the honey the bees will produce.

(Photo courtesy Rogue Ales)

Rogue also uses its honey in a Kölsch-style beer that has won a honey beer competition the Honey Board organized each of the last two years. “Honey has an incredible taste of place,” says company president Brett Joyce. “The honey from the hives on our farms doesn’t taste like the honey made anywhere else, and that uniqueness shows up in our beers.”

(Photo courtesy Service Brewing Co.)

Ryan likewise seeks to tap into local terroir at Service Brewing, where he makes a braggot as well as several honey beers. He ferments those, including Old Guard Bière de Garde, with a local wild yeast strain. He worked with SouthYeast Labs in South Carolina to set out 25 yeast traps near the brewery, then chose a strain taken from a cutting of honeycomb that had both pollen pockets and capped honey.

He calls another beer Scouts Out Honey Saison. You don’t have to be a honeybee to understand.

Saving the Bees One Hop at a Time

Of course it is coincidence that beta acids found in hop cones kill mites, a major pest for honeybees. But it is a happy one. The Environmental Protection Agency approved a product called HopGuard II for use in all 50 states in 2017.

“The advantage of using a natural hop product is there is no contamination in honey,” Doug Hauke of Hauke Honey Corp. in Wisconsin wrote via email. “We sell most of our honey to breweries for honey beer.” Hauke manages 3,000 colonies that produce almost 230,000 pounds of honey, most of which MillerCoors Brewing buys by the tote.

Bees for Hire

More than 90 percent of all bee species are solitary bees. Unlike honeybees and bumblebees they do not live in hives. However, they are valuable pollinators.

Demand for them has surged in California because of colony collapse disorder (CCD), the phenomenon that occurs when the majority of worker bees in a colony disappear. Colony collapses have occurred throughout history, but the syndrome was given an official name in 2006 with a dramatic rise in the number of disappearances. In the six years leading up to 2013, more than 10 million hives were lost, nearly twice the normal rate of loss.

Many credit the attention the disorder received with boosting interest in backyard beekeeping, although the number of colonies bottomed in 2008. However, eacha of the 1 million acres of almond orchards farmers in California plant requires two hives, and California beekeepers can supply only a quarter of that. Instead, farmers rely on traveling honeybee keepers, who serve different regions during appropriate seasons, or solitary bees.

(Photo courtesy Watts Brewing Co.)

Watts Solitary Bees rents mason and leafcutter bees to individuals and commercial operations, such as almond farms in California. The company is based in Bothell, Washington, where Evan Watts recently opened a small brewery—Watts Brewing Co.

Watts, who works days as a software consultant, does not brew honey beers. He built a one-barrel brewery as “proof of concept” and if the model proves itself, he and a partner plan to invest in a 15-barrel brewing system. The lessons he learned from helping with the family business, he says, are indirect. “Managing a biologic process is the biggest similarity, raising the bees, creating an environment that suits them, it’s like treating your yeast right, getting a healthy pitch for the next batch.”

Pike Hive Five

ABV: 5%| Hopped Honey AleTasting Notes: The first whiff reveals a lactic sour note, and the first sip is assertive with orange and grapefruit hops. It’s the finish that brings on the honey. It’s smooth and rich, with hints of honeycomb, vanilla and caramel. The deeper you get into this beer, the more earthy it becomes. A grip of wheat and a classic hop characteristic build to complete a beer that is truly meant to be enjoyed outside on a spring afternoon. –John Holl

Off Color Class War

ABV: 9.5% | Gotlandsdricka-Style Ale w/ Honey, Juniper Berries & Pear-Wood-Smoked MaltTasting Notes: Approaching Class War as a “honey beer” doesn’t quite prepare you for what’s ahead—and the complexity of the pear wood’s smoke character is surprisingly endearing, a bit like beechwood’s if softer. The aroma might have you thinking Schlenkerla: a mix of campfire and sweet, almondy wood. While the juniper berries tend to stay hidden, the refreshingly herbaceous and potently smoked Class War has its honey play out as a rich, rounded underpinning. –Ken Weaver

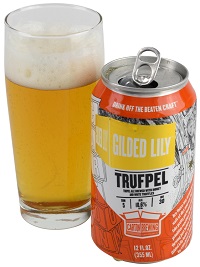

Carton Gilded Lily

ABV: 10.6% | Belgian-Style Tripel w/ Honey & White TrufflesTasting Notes: Even having your nose a few inches from the glass, there’ll be no mistaking the earthy funk of the truffles. Never had them? It smells like feet. But, there’s an appealing forest, garliclike flavor and, as you acquire the taste, you’ll almost understand why people pay so much for them. When brewing with honey, the flavor and mouthfeel often gets washed out, but in this ale it’s hearty and sweetly vibrant. The base beer has some spice and Belgian yeast characteristic, giving this fun complexity. It’s almost a meal in itself. – John Holl

Stan Hieronymus

Stan Hieronymus writes about how brewers may use hundreds of ingredients, including honey, to add local flavor to their beers in Brewing Local, his most recent book from Brewers Publications.

Leave a Reply