Beer Treasures

U.S. Museums Are Preserving Beer's History

Drinking beer is very much an in-the-moment experience. Bottles are opened, pints are poured, glasses are emptied, and the whole process repeats countless times a day. For many drinkers and brewers, beer is at the forefront of their minds as they continually look toward the next round and style.

However, for all the forward momentum the industry has today, little is being done to preserve its history. Here in the United States, largely due to Prohibition and its negative impact on beer, much of the memorabilia and interesting artifacts of breweries past were not retained or treasured. While countries like Germany, the United Kingdom and Belgium have dedicated national museums to beer, few similar institutions exist on American soil. Similarly, the brewers of today are not always acting with their eventual history in mind.

However, not all hope is lost. With a rebounding and vibrant beer industry, the rush is on to reclaim America’s beery past. In all corners of the United States—a cache of 19th-century bottles on display at the Brooklyn Brewery, Houston’s Magnolia Ballroom collection of “found art” depicting the milieu of beer-swilling Texas saloons, the weird rigs and historical artifacts of gold-rush era brewers exhibited at Alaskan Brewing Co. and so on—strong evidence of this preservationist movement can be found.

Seattle’s Pike Place Brewery is home to an extensive beer-history collection called the Breweriana Museum.

“The 9,000-year history of beer is rich,” says Charles Finkel, co-owner of Pike Brewing Co. and the enclosed breweriana museum, which, in 2008, was named the city’s best local attraction by both the Seattle Times and the Post-Intelligencer.

“Beer was one of the earliest items to be commercialized and is believed to have precipitated the world’s first advertisement—a stone carving featuring amply breasted Sumerian women extolling the virtues of ‘Lion Beer,’ ” says Finkel. “A Trappist brewery opened in Massachusetts last year. History repeats itself. If we want to predict what lies ahead, it’s important for us to understand what came before.”

Before Prohibition, brewers of all sizes were eager to create and disseminate collectibles. From serving trays to die-cast models of delivery trucks and brewery buildings, tobacco pipes, matchbooks and signs of all sizes in materials from tin to porcelain and hand-carved wood.

Many of the collectibles that survived now rest in private hands. Breweriana collectors regularly meet to buy, trade and ultimately collect bits of brewing history. From coasters to cans and bottles, some remarkable personal collections exist. They’re a source of pride for the owners, but the public rarely gets a peek at these artifacts.

Today, America’s brewers are largely struggling to keep up with customer demand, and logoed items offered for sale are largely of the T-shirt, baseball cap or pint glass persuasion. Fine souvenirs to commemorate a brewery visit, but unlikely items to stand the test of time.

It’s not just collectible items that are getting the short shrift, many brewers also don’t even take the time to take photographs of milestones or write down short notes about important-to-them historic moments that could one day be of interest to a wider audience.

“In the midst of the craziness, I think a lot of people neglected to think about it,” says Peter Bouckaert, brewmaster at Colorado’s New Belgium Brewing Co. “Here in Fort Collins, we’ve had at least four breweries close down that probably are only documented in people’s minds.”

“The thing is, in this industry, time flies,” adds Finkel. “Brewers are making history with each and every beer, label, coaster, festival, dinner and so on. It’s important to record and save what is created. And while I’m not suggesting every brewery should have a museum like Pike has, I do think brewers should recognize the importance of recording their history. The investment is small, but more than worth it.”

So, how will the legacy of today’s beer culture look, 15 to 20 years in the future?

“I think the enduring companies will be the ones that develop the story of their brewery’s culture within a context of community,” says Steve Hindy, co-founder of the Brooklyn Brewery. “These successful companies will be the ones that make beautiful, great-tasting beer that customers find exciting, while positioning those customers amidst the unfolding story of the brand.”

Which means?

“These endearing breweries?” says Hindy. “They will have meticulously, consciously and steadfastly crafted their own legacy.”

Here, now, are several of the spots across the United States that are preserving and displaying the history and culture of beer.

Steins Unlimited in Pamplin, Virginia is home to more than 9,000 historically significant beer steins. (Photo courtesy Annie Laura of 621studios.com)

Steins Unlimited

Pamplin, VA

Deep in the lolling, bucolic foothills of Virginia stands what may well be the nation’s most avid—albeit nearly unknown—monument to the history of beer vessels: Steins Unlimited.

The museum—a one-story brick ranch-style house with a shed outback—is nondescript, save for the tiny, hand-painted sign announcing the “Home of the World’s Largest Stein!” hanging from the mailbox. Steins Unlimited is home to more than 9,000 historically significant beer steins. With some dating back to A.D. 1200, barring the occasional absurdist oddity, the majority of the vessels are beautifully decorated, featuring ceramic bodies and pewter lids.

The collection is the passion of George Adams, the museum’s proprietor, who has spent the better part of the past 50 years scouring the planet, seeking out the oldest, rarest and most valuable beer-drinking vessels in existence.

Pamplin is about 30 miles east of Lynchburg and home to 219 residents, according to 2010 census numbers. Despite Steins Unlimited possessing neither a website nor a Facebook page, upward of 2,000 visitors manage to arrive at 616 Swan Road each year to ogle the self-proclaimed museum’s elaborate array of steins.

For those who find their way to Adams’ doorstep, it’s hard to avoid getting wrecking-balled by the eerie sense there is something big and strange and kind of fundamentally profound going on here. First off, Adams—serving as museum curator and tour guide extraordinaire—offers interested and legally aged patrons a “bottomless pint” of Coors Light or Yuengling lager, poured straight from the kegerator.

Walking toward the tin-roofed and clapboard-sided building housing one of the main exhibits, the 75-year-old explains how this shrine to beer vessels came to be.

“In the kitchen of my childhood home there hung this fabulous wooden cup thing with a lid,” says Adams, flicking on the lights as he walks through the screen door. “Eventually, I pointed at it and asked, ‘What’s that?’ To which my mother replied, with a shrug, ‘Oh, that’s Great-Grandfather’s stein.’ From that instant, aged 8 and onward, I was hooked.”

When the long, unfinished structure’s fluorescent tubes blink to life, they illuminate an array of tiered, floor-to-ceiling shelves brimming with steins.

“This section is arranged chronologically,” explains Adams, his pointer-finger trolling from right to left, indicating the sequence. “It opens with the late 19th century, in the era of Otto Von Bismarck, when Germany was a unified state, then proceeds onward through the war years.”

The heart of the collection is a 3,000-piece exhibit chronicling the history of German stein-craft from the inception of the Reinheitsgebot in the 14th century through World War II. His collection then takes a turn to the west and purportedly includes every stein Anheuser-Bush has ever produced, including a mid-’70s “Bud Man” prototype.

“Right now, this piece is only rumored to exist. Let the cat out the bag and I’ll have to deal with collectors phoning me night and day, begging me to sell!”

With paternal delicacy he cradles another ceramic, pewter-lidded vessel from its perch and, holding the object at a distance (to better utilize his bifocals), like a man gazing into a beloved photo, he sighs, delicately fingers its design—a horse-drawn fire wagon manned by heavily mustached, sternly uniformed men, bustling from the garage of a brick, bell-towered firehouse onto a cobblestone drive, b-lining for a group of faraway, hill-topping bungalows (rendered in perspective), one of which spews into the starry horizon a plume of billowy, orange-tinged smoke.

“During this period—1871 to 1914—steins were a very social phenomenon,” says Adams. “At the end of your workday, you would go to your local stupa, upon which your friends, family and acquaintances would all be converging, have the barman or maid retrieve your personal stein from the wall,and fill it with your favorite draft, which would typically have been brewed on-site.”

It was a different time than now, when bars typically serve beer from a homogenized pint glass featuring the logo either of the establishment or a beer brand.

“But back then,” he says, giving the stein in his hands a tender pat, “for your average 19th-century German, his drinking vessel was a matter of sincere importance. His stein was a cherished, personalized and highly significant article. In the era in question, the steins tended to be first heraldic, familial. …” Pointer finger extended, he taps on first a coat of arms hovering regally over the firehouse, second the horse-drawn fire engine “… and then professional. A fellow’s stein would’ve featured something of the story of his life.”

Steins Unlimited is open seven days a week from 9:00a.m. – 5:00p.m. Adams does not maintain a website for the museum, but may be reached at (434) 248-6114.

Pike Brewing Co.

Seattle

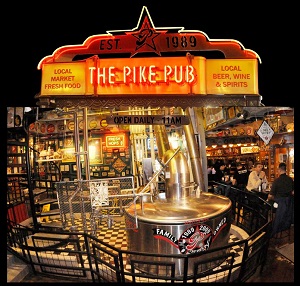

Hard against Puget Sound in Seattle is the Pike Place Market, a hub for the fishing industry, favorite spot of tourists and a place to get quickly caffeinated by one of the countless coffee shops. In the center of a building that houses an indoor mall is the Pike Place Brewery. With its gravity-powered, three-story-tall, 30-barrel brewing system serving as a centerpiece, Pike has been a cultural and comfortable stop since Charles and Rose Ann Finkel opened in 1989. It’s also home to an extensive beer-history collection.

On an overcast morning several months ago, Finkel walked into the brewery, a few minutes before a scheduled interview carrying a canvas bag filled with mounted memorabilia. He unloaded the contents—coasters, a few matchbook covers, some bottle caps—onto his desk, adding them to an already large pile of black-backed plaques with clear heavy plastic covers that he creates at home from items he deems worthy of his collection.

These items will soon join the already crowded walls of the brewery, what is known as the Breweriana Museum, which gets just as much attention from visitors as the beer in their glasses.

Finkel regularly searches catalogs, antique shops, the Internet, etc., seeking all breeds of beer memorabilia—a category including but not limited to tap markers, matchboxes, defunct signs, old advertisements, bottles, caps, pipes, fishing lures, flashlights, barrel-shaped clock radios and so much more—to add to the collection. The museum has what might be the largest collection of sheet music dedicated to drinking songs. If the likeness of King Gambrinus was placed on something, chances are he has that as well. He takes special pride in finding items relating to historic U.S. breweries, regardless of corporate ownership.

“When Miller sold their collection, we were able to acquire some great items,” says Finkel. “This disregard for their history is a metaphor for the relationship these global companies have with the culture of beer. They are factories that manufacture a commodity, which they then advertise. And their sales and diminishing customer base are reflective of that discrepancy.”

The brewery does sell the usual trinkets, but Finkel has also added things like handmade bottle openers, coat hooks, special glassware, and, yes, beer trays: items built to outlast its first owner.

The National Brewery Museum opened in 2008 in a building that formerly housed the Potosi Brewing Co.

National Brewery Museum

Potosi, WI

Potosi is nestled between historic U.S. Highway 61 and the Mississippi River. The town was founded by miners, German farmers soon moved in, and by 1852 Gabriel Hail began brewing lager beer to quench their thirsts. In the 1880s, he passed the brewery to the Schumacher family, who continued to expand the complex and the brand (it was named Potosi Brewing Co. in 1905) until 1972, when they reluctantly closed—unable to compete with the industry giants.

Like many defunct breweries, the building lay idle for decades, but unlike most, it gained a second life. A group of local residents formed the Potosi Brewery Foundation to buy and restore the building, and then partnered with the collectors of the American Breweriana Association (ABA) to establish a museum in the complex. Restoration began in 2004, and the museum complex and brewpub opened in 2008.

There are actually two museums housed in the restored brewery. The Potosi Brewing Co. Transportation Museum (on the ground floor) integrates the story of the brewery into the broader tale of moving goods and people along the Great River Road corridor. Exhibits show how wagons, trucks and even a steamboat made “Good Ol’ Potosi” beer a popular brand in the region.

The National Brewery Museum occupies most of the rest of the building and will impress anyone who ever saved a glass or coaster from a favorite beer. The central gallery features the Schuetz Collection—an astonishing assortment of artifacts, many of which were saved from small-town Wisconsin breweries after they closed in the 1950s or 1960s. Rare neon signs hang above cases filled with old trays and art deco back-bar lights. Giant 19th-century brewery lithographs and metal signs decorate the walls.

But the primary goal of the National Brewery Museum was to be a “members’ museum”—a place where ABA members could show off portions of their collections to a wider audience. Visitors may see exhibits on world-famous breweries like Pabst or Anheuser-Busch, or on small breweries from around the country that still produced an amazing array of advertising pieces. Since these exhibits rotate every 18 months or so, there will be something new to see with each visit.

The Potosi Brewing Co. brewpub is decorated with Potosi breweriana and is a great place to enjoy a beer and contemplate the history the beer. A new production brewery and taproom are scheduled to be open by summer 2015.

Brooklyn Brewery displays more than 80 bottles that document New York City’s brewing past. Here, co-founder Steve Hindy points at one of the brewery’s displays.

The Brooklyn Brewery

Brooklyn, NY

The Brooklyn Brewery, which attracts thousands of visitors each year, knows its place in New York City’s proud beer history. To remind guests of what came before, there is a display of nearly 80 bottles that document the city’s brewing past.

Many of the bottles came from an attorney who lived in Queens and contacted Hindy shortly before the brewery opened. “He put together this collection over a lifetime,” says Hindy. “He said, ‘When you open your brewery, I’ll lend you the collection to display.’ So when we opened our building in 1995, I called him. He said he was retiring to Florida and his wife wouldn’t let him bring the bottles, so I bought the collection for like $1,200, and he and his wife were very happy.”

Hindy has learned much about the history of the city’s beer through the medium of glass. The collection represents all the breweries he could find information on, like the year opened, volume output and more. There are still some other bottles that represent breweries that never made the history books.

What is fascinating about the collection is that there was once a handful of breweries that were big, regional forces, like Schaefer and Rheingold, and still dozens that were very small. Today they are all gone. Finding bottles that represent these breweries from the 1800s and 1900s is quite the feat itself.

Historically, says Hindy, “the deposit on the bottle was a quarter, the beer itself cost a nickel, so the bottles were more valuable than the liquid.”

The Saint Louis Brewery, which produces Schlafly beer, has a room filled with breweriana from historical Saint Louis breweries. (Photo courtesy Troika Brodsky)

Schlafly Bottleworks

St. Louis

Even as the city’s beer scene rebounds today, there are many people who can only think of one brewery when it comes to St. Louis: Anheuser-Busch, makers of Budweiser. Yes, the country’s largest brewer dominates the consciousness and the skyline, thanks to its huge brewing complex. But, historically, there was much more to the city’s brewing past. When the Saint Louis Brewery (which makes Schlafly beer) was creating a space where visitors would gather for the tour several years ago, it turned to then-spokesman Troika Brodsky to fill a room with St. Louis breweriana.

“Historically the city had over 200 breweries, but people don’t fully understand that our history is more than A-B,” says Brodsky. So, with the help of local collectors, he set out to gather as much history as possible. The space now contains everything from old lithographs to porcelain shields that served as signs. There is even a stone bottle that was unearthed and “the only evidence this one brewery ever existed.”

Now, as visitors sample the house beers, they can watch vintage commercials on a television, read old advertisements, explore eras through labels and get a deeper sense of what this proud city has contributed to the country’s beer history.

Other Points of Interest

The American Hop Museum

Toppenish, WA

The Yakima Valley has produced some of the finest hops in the world, and its bounty has inspired generations of brewers. With rotating exhibits and featuring antique harvesting equipment, the museum chronicles the history of the hop industry from early America to the modern-day boom. americanhopmuseum.org

The Herb and Helen Haydock World of Beer Memorabilia Museum

Monroe, WI

Located at the Minhas Brewery, and valued at over $1 million, this is a collection gathered by renowned breweriana enthusiasts. According to the brewery, it features “hundreds of brewery advertisements from the past, lithographs and prints from the mid 1800-era” along with “a collection of tap handles, growlers, model cars, trucks and trains from all around the world.” minhasbrewery.com/brewery-tour

The Brewseum

The Brewseum

Honolulu

While the owners call it the Brewseum, visitors to this island bar won’t find much in the way of breweriana. Rather, this monument to World War II memorabilia keeps the memory of the Greatest Generation alive while giving patrons the chance to knock back IPAs, stouts, pilsners and more. There’s even a plan to install a one-barrel brewing system. brewseums.com

Eric J. Wallace

Eric J. Wallace is a freelance writer. For inquiries, overly intimate newsletters, or to learn more about his work, visit ericjwallace.com.

John Holl

John is the editor of All About Beer Magazine and the author of three books, including The American Craft Beer Cookbook. Find him on Twitter @John_Holl.

Doug Hoverson

Doug Hoverson is the author of Land of Amber Waters: The History of Brewing in Minnesota and a book on brewing in Wisconsin to be published in the fall of 2016.

check out my brewery museum in framkenmuth,mi. ”THE LAGER MILL BREWERY MUSEUM