For a baseball fan growing up around New York, the Sixties was an enchanted era. On summer nights, the radio filled my room with the sounds of epic pitchers’ duels, bench-clearing brawls, and late-inning heroics. And, of course, beer commercials. Thousands of them. Long before they could serve me at the corner tavern, I knew that Schaefer was “the one beer to have when you’re having more than one”; Rheingold was “not bitter, not sweet”; and the Ballantine rings stood for “purity, body and flavor.”

The beer still flows at major league parks. But it’s not the same beer our fathers drank.

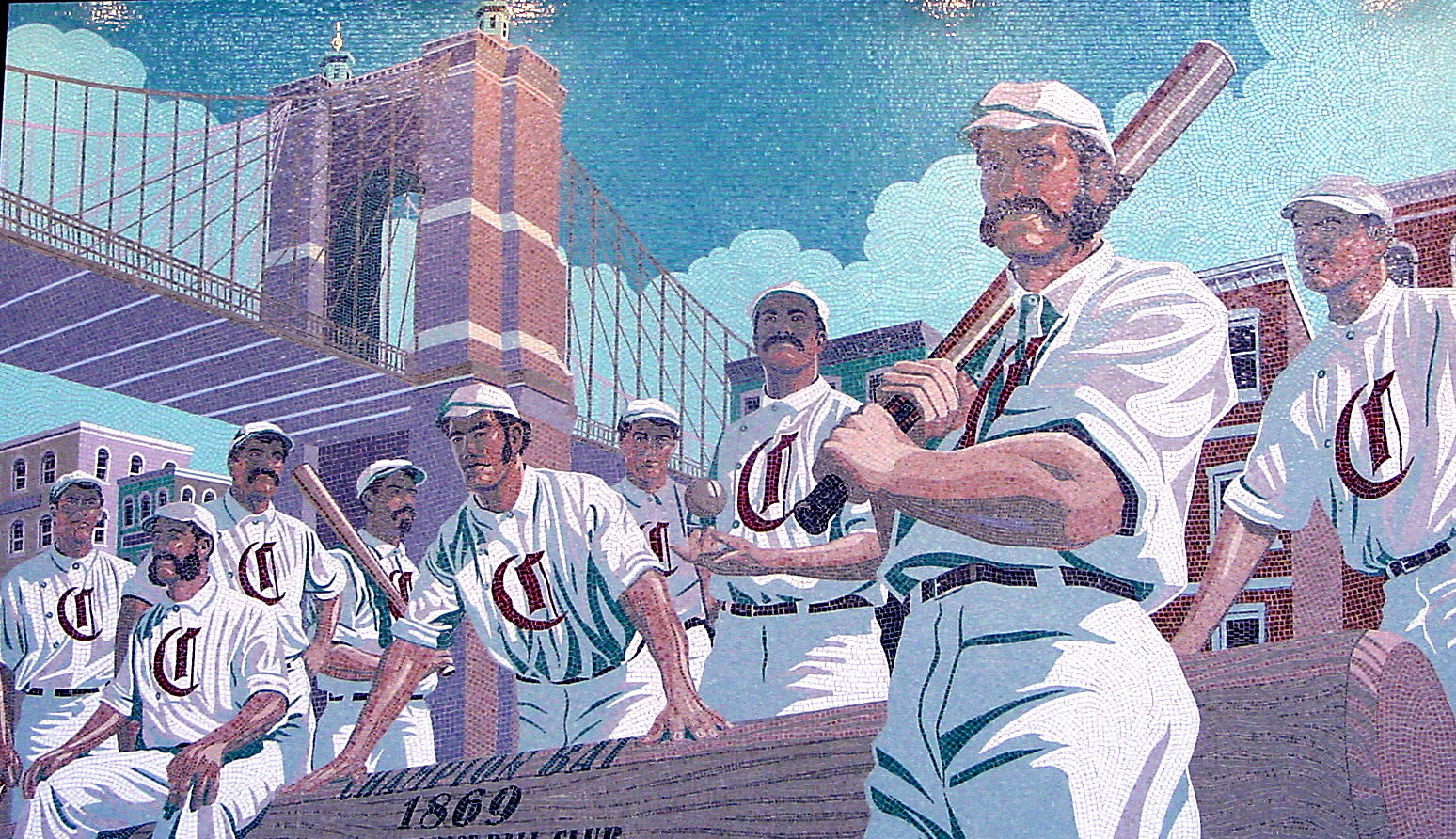

Mural of “old-time baseball” inside Cincinnati’s Great American Ballpark. (Maryanne Nasiatka)

My formative years weren’t unique. A college buddy from Pittsburgh cracked me up with his impression of Pirates announcer Bob Prince telling fans to “Pour on the Iron,” referring, of course, to Iron City beer. A White Sox fan swore to me she’d once seen Harry Carey downing a few with the Comiskey Park bleacher creatures—this while broadcasting the game. And my Michigan neighbors fondly recall Ernie Harwell imploring them to “hang on to your Stroh’s” when the Tigers called on their bullpen to save a close game.

Beer is not only part of baseball’s lore but also a tradition older than the National Anthem, the seventh-inning stretch, and even the World Series. It began in 1882, when saloon owner Chris Van der Ahe bought the bankrupt St. Louis ball club, renamed it the Browns, and joined the upstart American Association. Van der Ahe was the Charlie O. Finley of his era. Part of his marketing strategy was to cut the price of admission to a quarter. Smart move: he made his money back and then some, in profits from his beer garden. It wasn’t long before the Browns became a powerhouse, both on the field and at the bank.

Beer and Baseball Barons

Van der Ahe wasn’t the only beer baron to own a baseball team. Colonel Jacob Ruppert bought the New York Yankees and launched the greatest dynasty in sports history; ironically, he did so during Prohibition. Augie Busch shook up the baseball establishment when he acquired the St. Louis Cardinals; later, he made the Budweiser Clydesdales part of the game-day entertainment. For a while, the Labatt Brewing Co. owned the Toronto Blue Jays. And while Miller and Coors don’t own teams, their names can be found on the marquees of major league parks.

While baseball has changed over the years—we now have the designated hitter rule, dancing mascots, and month-long playoffs—the beer still flows at major league parks. But it’s not the same beer our fathers drank. The breweries whose jingles filled the airwaves became casualties of post-World War II consolidation, giving way to national brands that came to dominate the industry. But recently, ballpark beer has come full circle. Local beer is back.