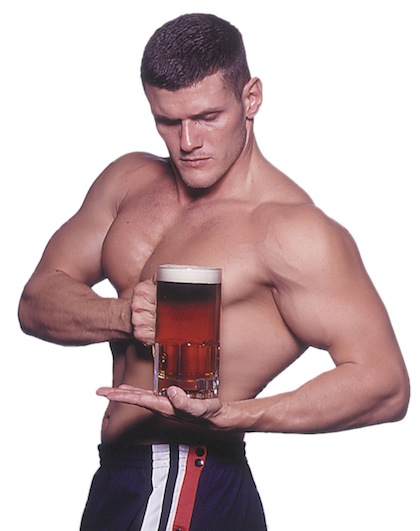

Biggest. Brightest. Loudest. Strongest.

“It’s not just about maximizing alcohol. If it were, you’d be drinking Everclear.”

In nature and in life, flamboyance commands attention. Any animal species with the power to discriminate distinguishes between those of its kind with more and those with less of that certain something–feathers, muscles, songs, colors, teeth–and the Mores usually win.

(Kinsley Dey)

We may express admiration for subtlety, but when did you last get really excited about the smallest, the slowest, or the most delicate? No, be honest: it’s the loudest fanfare, the tallest plume, highest leap, the hottest pepper that really grabs your senses and makes you gasp. That is where the tension is, because the triumph is fleeting: the fastest runner is only the fastest that’s ever been, not the fastest that can ever be. Records are made to be toppled.

The strongest beer. When it comes to alcohol, the fascination with just how strong a beer can possibly get runs slap up against the party line on alcohol restraint. We are not meant to rave about strong drink just because it’s strong: hence the beer reviewer’s fondness for euphemisms like “very warming” (translation: “gawd, that’s strong”).

The search for the most intoxicating beer seems to go to the heart of all our contradictions about alcohol. But the truth is, the quest for the strongest beer isn’t really about getting you drunk, any more than the world weightlifting championships are about moving big pieces of metal from one place to another, or the grand slalom is about the quickest way down a hill. Alcohol content, weight, speed: they are all proxy measures of the skill and discipline of the practitioner.

Jim Koch, whose Boston Brewing Co. created Millennium, the current record-holding beer, said, “It’s not just about maximizing alcohol. If it were, you’d be drinking Everclear.”

Contest Rules

Like an Olympic event, the contest for strongest beer has rules. Unlike the Olympics, the participants don’t necessarily subscribe to the same set of rules. Must the beer be made only from malted barley? Adherents to the Reinheitsgebot, the Bavarian Beer Purity Law of 1516, regard brewers who stray from the all-barley path the way a purist body builder regards steroid junkies. To them, these are unfair “performance enhancers” that show nothing of the brewer’s craft.

Dan Shelton, who imports the German beer EKU 28, says of German tastes, “Simply put, a top-fermented beer using non-malted fermentables is not beer to a German. . That is exactly what the German export agent told me. When I mentioned that there were other beers out there from Belgium, Holland and France now claiming to have higher alcohol content than the 28, he said, “Ja, but that isn’t beer for us.’”

What about yeast? Does the yeast that creates the world’s strongest beer have to be, traditionally, a beer yeast? Top fermenting? Bottom fermenting? What about wine yeast? Champagne yeast? Funky stuff out of the yeast archives? It may ferment beautifully, but is the result beer?

Making the world’s strongest beer is not about making the world’s finest beer–very strong alcohol may indeed preclude greatness. And yet, all the beers that have been called “the world’s strongest” have also been admired as awfully good beers. Michael Jackson pokes gentle fun at the scramble for supremacy, but acknowledges the quality: “While this contest [for strength] is too hard to resist, such muscle has limited application. These are beers of excellent quality but they would best be dispensed from small barrels suspended from the necks of mountain-rescue dogs.”

That may, in fact, be another unwritten rule of the Strongest competition: it’s got to be good to drink. As Grant Wood, production manager at Boston Beer Co. and leader of the team that created Millennium, put it, “The big fear on my part was that, yes, we would break the world record, but we would have produced something that tasted vile, sort of a cross between an IPA and airplane glue.”

So, the strongest beer in the world must be measurably strong. It must be brewed according to rules. And it has to taste pretty damned good.

A handful of beers–six or seven–have had a legitimate claim to call themselves “the world’s strongest beer” in the past half century. Check the books today, and you’ll find one beer singled out. But each title holder was in its time stronger than any beer that came before. So it seems only fair to honor them in chronological order, like the kings of England, or the begats of the Old Testament. After all, this is brewing on an epic scale.

The Nature of the Challenge

Brewing strong beer all comes down to the care and feeding of yeast. These single-celled organisms consume sugar for fuel, and produce new yeast, plus carbon dioxide and alcohol–that’s fermentation. From the point of view of the yeast, producing more yeast is what’s going on; the carbon dioxide and alcohol are waste products. From the point of view of the brewer, though, the waste products are the purpose of the whole exercise.

The challenge for the brewer, then, is to keep the yeast operating in greater and greater concentrations of alcohol, what brewers variously called “a hostile alcohol environment,” or “a hideously poisonous atmosphere.” To the yeast, it must be like living in Los Angeles during a temperature inversion, choking on your own pollution.

As the alcohol concentration rises, fermentation slows, then stops. The yeast can’t take anything in, and they can’t excrete. They use up their internal stores of energy, then die.

How can a brewer keep the yeast ticking over for as long as possible? All the strong beers have taken broadly similar routes.

First, the brewer chooses a yeast strain (or more than one) that is relatively alcohol tolerant. For some breweries, this has meant searching outside traditional beer yeast strains and borrowing from vintners and distillers. It can also mean pilot efforts in micro-evolution, selecting and breeding the hardiest yeast cells over several generations.

Then, the ideal diet. The wort–the sweet broth that sustains the yeast–needs to be packed with nutrients. Original gravity (OG) is the measurement of the concentration of dissolved material in the wort. Brewers from the German tradition follow the letter of the Reinheitsgebot, which stipulates that only barley can be used as the basis of the wort. Brewers from other traditions boost the starting potency of the wort–the original gravity–with other grains or sugars.

Finally, time and temperature. To ferment this super-strong wort until as much of the sugar as possible is turned into alcohol can take months, and tends to work better at low temperatures.

First of the Strong

Erste Kulmbacher Union Brewery–EKU–in Kulmbach, Germany, trumped a local competitor when they created EKU 28, the first beer promoted as the strongest beer in the world or, rather, “das stärkste bier der Welt.”

Since the beginning of the last century, Kulmbach has had four commercial breweries, including EKU and the rival Reichel brewery. According to importer Dan Shelton, “The town just isn’t very big. With such a small immediate market, the great breweries of Kulmbach were surely locked in fierce competition for ages.”

Hermann Nothhaft, braumeister at the Kulmbach Brewery, explains how EKU 28 was born of cross-town rivalry. In 1905, the Reichel brewery brought out the original eisbock, a traditional bock beer made stronger by freezing the water and removing ice to concentrate the alcohol.