The United States of Style

Historical, Cultural Influences Help Beer Styles Find a Home

All across the U.S., drinkers have no trouble finding an IPA. The popular style is ubiquitous from the bars and breweries of New England to the beaches of San Diego.

But move from city to city and you’ll find an increasing trend: Breweries are putting emphasis on sharing where a beer is coming from almost as much as what goes into it. Maybe it’s a weisse showcasing a fruit popular in Florida or a regional calling card of wheat from the nation’s breadbasket. New England-style IPA and San Diego Pale Ale both may use plenty of hops, but each marks its own territory, signaling uniqueness in creation, philosophy and even marketing.

When it comes to what’s “local,” brewers are working to show off pride in what separates their nook of America’s beer landscape. Whether it comes from a recipe or a cultural mindset, they’re trying to define what it means to be a regional beer.

In July 2015, Matthew Zook wanted to show just that. Zook, a professor in the department of geography at the University of Kentucky, released a set of findings aptly titled “#BeerTweets,” an interactive visualization of billions of geo-tagged tweets, each a new data point of America’s beer-related tweeting contained in 140 characters or less.

With shades of blue filling up hexagons across a map of the United States, it was possible to see how tweets might contain textual references to a particular beer brand, like New Belgium’s Fat Tire, and even beer style.

Zook found some expected results: “Brooklyn Lager” popped up all around New York City, and Texans loved tweeting most about Shiner Bock, made in Shiner, Texas. But it became clear that while specific beer brands received lots of interest in areas where they originated, entire styles of beer showed strong correlations to particular states and regions of the country.

“Stout” was heavily mentioned in Northern states typically hit with bitterly cold winters, and “wheat ale” got the most comments up and down states of the Midwest, including some found inside America’s Grain Belt.

“When we got to looking at styles, it started to get at a deeper cultural identity that’s not just about business marketing,” Zook says.

The idea of beer styles specific to a region—or even brewers looking to establish a localized kind of beer to hang their hat on—isn’t new. There are all sorts of cultural and geographical influences that have given beer lovers styles like altbier and Kölsch, which originated in Germany but have since spread throughout the world. That kind of cultural diffusion came to a head in November 2015 for North Carolina’s Olde Mecklenburg Brewery, which won a gold medal for a Märzen at the European Beer Star Competition, beating the Germans at their own game.

So at a time when a given kind of beer can be found just about anywhere in the world, breweries are finding a way to double down on what it means to drink local by brewing local with ingredients, methods or philosophy that makes beers unique to the place they’re made.

It’s what Jeff Alworth calls a “distortion field,” a cultural influence so ingrained in one geographic pocket that it simply becomes part of a localized identity. He saw it during research trips around the globe to better understand the background of about 80 beer styles for his latest book, The Beer Bible.

In Germany, it’s aromatic, flavorful base malts. In Belgium, it focuses on warm secondary fermentation. Across the U.S., areas of distortion increasingly emphasize hops for late-addition, post-kettle and dry-hopping. In each case, it’s an opportunity for brewers to coalesce around a particular approach (or approaches) to brewing, even if the resultant beer could also be made on the other side of the world.

“In the United States, localness was the norm until hops and barley became a national market, which cut into the idea of regional quality,” says Alworth, who is also a columnist for All About Beer. “But brewers in a place like Portland still influence each other way more than somebody from out of state, even as the world has shrunk.”

Which may help explain those tweets. While a beer’s ingredients determine its tastes and aromas, so too does its cultural identity. Across the country, brewers are finding ways to tie their creations not only to what goes into each batch, but also to how that brew might interact and engage with their drinkers. For many, it’s about a beer that connects to a place through flavor and experience.

Celebrating Florida’s Fruit

This idea is perhaps most easily found in the Sunshine State, where Florida’s brewers and drinkers have taken a foreign style and added a twist unique to their area.

The “Florida weisse,” a spin on the traditional German style of Berliner weisse, finds a perfect balance for the state by mixing the beer’s low-ABV style with tropical fruits native to Florida. The style came to fruition in 2009 at Gulfport’s Peg’s Cantina and Brew Pub and in 2015 was further popularized in Miami with a fierce dedication by J. Wakefield Brewing.

“We’re living in 95-degree weather down here, and dark beers—besides maybe some big imperial stouts—don’t do well because people want something light and refreshing,” says Jonathan Wakefield, owner of J. Wakefield. “This style incorporates a lot of what is ‘Florida’ by using local ingredients and benefits from our weather and climate.”

In recent years, fruited weisses can be found from breweries like Massachusetts’ Night Shift Brewing, Michigan’s New Holland Brewing Co. and Oregon’s Bend Brewing Co. But Wakefield says the style has become entrenched into part of the brewing culture in Florida.

“Grain doesn’t grow out my back door, so this is a way we can define our beer as ‘local,’” he said.

At J. Wakefield, up to six Florida weisses appear on tap each week, including favorites like Miami Madness, made with mango, guava and passion fruit, and Keyboard Muscles, which uses starfruit. Other Florida-inspired weisses can be found at Tampa’s Angry Chair Brewing and Dunedin’s 7venth Sun Brewing Co.

In August 2015, Wakefield hosted the fourth Florida Weisse Bash, which featured 11 breweries sharing home-state-inspired Berliner weisses made with flavors of key lime, tangerine, dragon fruit and passion fruit. Pucker-inducing flavors may have attracted about 600 beer lovers to the event, but it’s what the beer stands for that makes the style so popular, Wakefield says. At a time when “local” is synonymous with consumer choices across a range of products, the Florida weisse puts an unmistakable stamp on a beer unique to Floridians.

“Outside of Florida, I don’t know where else you’re going to find dragon fruits, but I can go 20 minutes from my brewery and find them, along with lychees, mangos and guava,” Wakefield says. “Our state industry is still fairly young, but it’s good for us to have some kind of unified voice behind a beer.”

A ‘Distinctive’ Taste of Hop Freshness

Nearly 97 percent of America’s hops are strung for harvest in Idaho, Washington State and Oregon, with the Hop Growers of America estimating 43,987 acres in the three Pacific Northwest states in 2015. Each fall, beer lovers can drink fresh-hop beers just about anywhere in the U.S., thanks to the farmers now growing the crop coast to coast, but they may be harder pressed to find the kind of distinct representation of a fresh-hop beer away from its agricultural epicenter.

“A lot of people may focus on East versus West Coast IPAs, but this is one of the most distinctive American expressions,” says Alworth, who has called Portland, Oregon, home since 1986.

Though it is typically brewed in the style of pale ale, the defining characteristic of a fresh-hop beer is in its name. Around late August and early September, hop cones are plucked from fields and immediately transported to nearby breweries, as early deterioration starts the moment a cone is taken from its bine. First popularized by Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. in the late-’90s, the fresh-hop beer has been made a seasonal credo by brewers in Oregon and Washington, thanks to nearby farms growing the vast majority of the country’s hops—a defining crop for brewers of the Beaver State.

A celebration of the style takes place every fall when cities across Oregon host fresh-hop beer festivals. In 2015, at least seven took place in the state, from small cities like Sisters —population about 2,200—to Portland, the state’s largest city.

(Photo by Silvia Flores)

For the 2015 harvest, Double Mountain Brewery, located in Hood River, Oregon, rented a 24-foot-long refrigerated truck to drive two hours to Sodbuster Farms in Salem. In less than an hour, brewery owner Matt Swihart and another staff member collected about 1,400 pounds of Perle hops and hightailed it back to the brewery, where brewing would take place 24 hours a day for three straight days to make 15 batches of Killer Red fresh-hop beer. The process was later repeated to collect over a ton of Simcoe and Brewer’s Gold hops for a second beer, Killer Green.

“Outside of the state, some breweries get hops frozen and overnight shipped, some get undried, but days old,” Swihart says. “But when you physically see hop degradation after 10 hours, you can’t beat the way our breweries are able to use them.”

Swihart estimates Double Mountain’s fresh-hop beers may have three times the usage rate of hops compared to other versions of the style found elsewhere, aided by the ease with which Oregon’s brewers have access to the crop and pushed further by the commitment of local brewers to create fresh-hop beers.

“It’s a style ingrained in the story of the Pacific Northwest,” Swihart says. “When I make these beers, I feel more like a farmer than a brewer, because the trick is our proximity to these fields.”

An American Original

In Kentucky, what’s old is becoming new again as a historical style catches on with today’s brewers and offers a way to reconnect with a beer that was once almost exclusively produced and sold in the state’s largest city.

The Kentucky Common, one of a small number of beer styles to originate in America, is now riding a growing wave of local pride toward resurgence in Louisville, where it first came to popularity. The malt-forward brew has a touch of floral or spicy hop character among its bready notes, and modern versions often include souring—a callback to the long-held belief that the original style offered a tart taste because brewers used a sour mash like their contemporary bourbon distillers.

According to Kevin Gibson, author of Louisville Beer: Derby City History on Draft, about 80 percent of beer sold in the Falls City was Kentucky Common before Prohibition swept the state in November of 1919. The style lay mostly dormant until around 2013, when it gained momentum among local brewers. Gibson notes the historical beer can now often be found as a rotating or seasonal offering.

“To me, Kentucky Common is arguably more Louisville than the Kentucky Derby or mint julep,” he says. “I love being able to walk into a brewery and know I’m getting something similar to what my great-great-grandfather might have been drinking.”

Original to the Louisville area, Kentucky Common became ubiquitous among working-class residents of the city by the early 20th century due to its low cost and quick production of about nine days, which allowed for transport while still fermenting.

(Photo courtesy Apocalypse Brew Works)

Today, a Kentucky Common may be found at New York’s Upstate Brewing Co., but Louisville is where the style is making a concentrated march back into pint glasses, signifying a celebration of the state’s brewing past and cultural heritage. The effort even has a leader in Apocalypse Brew Works, which makes a historically authentic take on the Kentucky Common made with a 1912 recipe found at Louisville’s now-defunct Oertel

Brewing Co.

“Brewers are always looking for ways to be different, unique and creative, and now we’re also looking back into history,” said Leah Dienes, owner and head brewer at Apocalypse. “This is about bringing something back to life.”

Thanks to a growing commitment to the style from local brewers, Kentucky Common is back in the spotlight. It got its own coming-out party during the weekend of the 2015 Kentucky Derby, when 13 state breweries created their own versions of the style to serve at the Derby City Brewfest. Also in 2015, it was added as a historical beer category within the Beer Judge Certification Program guidelines.

“It’s a really nice, important connection to the past,” Gibson says. “But it’s also part of the history of our city and state.”

Taking the ‘India’ Out of IPA

For today’s drinker, identifying one of beer’s most popular styles can be easy, especially if it happens to be packed with hop varietals like Cascade, Simcoe and Amarillo.

“But when did time stop and anything hoppy and over 6% have to have ‘India’ in its name?” asks Cosimo Sorrentino, head brewer at San Diego’s Monkey Paw Brewing and South Park Brewing Co.

Whatever the preferred moniker may be, Sorrentino isn’t alone. Even though India pale ales may be the hottest-selling style at many beer bars and breweries across the country, it also goes by another name in his city: the San Diego Pale Ale.

Monkey Paw’s Muriqui (10%) or Bonobos San Diego Pale Ale (7.9%) might be known as double IPAs in most other locations, but San Diego has been home to a decades-long game of “hops-upmanship,” says Sheldon Kaplan, a documentary filmmaker who directed the San Diego beer-focused “Suds County, USA.” The San Diego Pale Ale represents a collective thumbing of noses toward other areas of the country that don’t have the history or ingrained cultural fervor toward a particular brand of hop-forward brews.

“There was a shift away from balanced beers from East Coast breweries, and once people started to realize they were doing something completely different here, there was pride in something they owned,” says Kaplan, who’s lived in San Diego since 1996. “There was a certain ‘we don’t care what they think’ psyche.”

It was an attitude that was adopted with excitement in San Diego, where a hop-focused philosophy in the city passed between homebrewers and professionals alike, leading to pride and ownership of the San Diego Pale Ale and what it meant as a hometown beer.

“The style evolved here, and people are protective of it,” Kaplan says.

In 2012, the San Diego Brewers Guild made that feeling a tangible reality, collaborating at Karl Strauss Brewing Co. on a 10% beer named “San Diego Pale Ale” for that year’s Craft Brewers Conference. On its label, a tagline read “The flagship beer style of America’s finest hop heads.”

To Sorrentino, the low-malt, highly hopped style of San Diego pale ale should have minimal bitterness and plenty of juicy, tropical and citrus flavors.

That may sound like recipes used for IPAs made all over the country, but in this California city, the San Diego Pale Ale is meant to act as more than a sum of ingredients, Sorrentino adds. It reflects an attempt at ownership for a style popularized on the West Coast, held dearly by locals and acts as the place he considers historically pivotal for today’s love for hoppy styles.

“It’s about the weather and the lifestyle,” he says. “We want a light beer that carries as much flavor and aroma as possible that’s perfect for the beach and 65- to 75-degree weather.”

Amber Waves of Grain

Look across many Midwest states and one crop stands out when it comes to beer.

“Wheat is a recognizable ingredient and also heavily influences many local economies,” says Jeremy Ragonese, director of marketing with Boulevard Brewing in Kansas City, Missouri. “It’s a status symbol of the Midwest.”

So much so, advertisements for the brewery’s Unfiltered Wheat rely on the slogan “as Midwest as it gets” to conjure a specific feeling for a crop that plays heavily in the lives of Midwesterners. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, all but one of the 13 Midwest states were among 2014’s top-25 wheat producers and include five in the top 10.

“Around here, you might not always find an IPA on tap, but you always know you’ll find a wheat beer,” says Russell Brickell, head brewer 23rd Street Brewery in Lawrence, Kansas, consistently one of the top-five wheat-producing states in the country. “Wheat is what we’re known for, and people like that style as an identification for who we are.”

At 23rd Street, Brickell says, his Wave the Wheat beer is a top-three seller, partly because it’s a good gateway for nonbeer drinkers, but also because it represents a cultural attitude of Midwesterners as something they know and can rely on.

“We’re not the first ones to jump off and do something crazy,” Brickell says. “Wheat has been around here forever and people know it, which is why any brewery you go to around here has a wheat beer, and they all do really well.”

At Boulevard, Unfiltered Wheat made up almost 40 percent of production volume in 2015 and ranks as a top craft-defined draft placement in major Midwest markets like Kansas City, Omaha, Des Moines, Lawrence and Springfield.

Interest in wheat beers may translate to marketing and sales, but there’s a reason for that. Even though the style can be found just about anywhere around the country, both Brickell and Ragonese suggest the Midwest’s cultural connection to wheat make it a beer style that will always stand tall among its residents.

“The same way we see the idea of ‘local’ having a strong association for all kinds of goods, it’s no surprise consumers are seeking out things that embody a particular spirit of emotional connection to place,” Ragonese says. “Wheat is a historically American ingredient that evokes that feeling, which is an idea that is more deep-rooted than people may recognize.”

At Boulevard, it’s carried over into other beers, too. Unfiltered Wheat serves as the base for 80-Acre Hoppy Wheat, the company’s foray into West Coast-styled beer, and its Ginger Lemon Radler.

“There’s something true and authentic about trying to embody a sense of place,” Ragonese says.

Holding History

Which circles back to the idea of distortion fields mentioned by Alworth. In a country featuring more than 4,000 breweries and beer styles that can be imitated or replicated just about anywhere, there are still efforts by businesses to find ways to make their beer uniquely true to their home.

Focusing on this cultural aspect not only allows a beer to stand out, but also reflects a sense of place and the connections people want to create with something special to them—making a beer more than just liquid.

“When you hold a bottle of beer in your hand, you’re holding a little bit of history,” says Alworth. “You can learn a lot about the past by unpacking what the world around these styles means and how they came to be.”

That’s taking place right now in Durham, North Carolina, where Seth Gross, owner of Bull City Burger & Brewery, is trying to lead the charge to create the city’s own beer style, called “The Durhamer.”

Gross’ team brewed the first batch of the malt-driven beer in November, and at least four other breweries in Durham have agreed to make the beer according to guidelines created by Gross. The Durhamer calls for an ABV of 5.2%, filtered but untreated Durham water, locally sourced malt and hops as available and ale yeast.

The beer’s light sweetness is an homage to the South’s love for sweet tea, but most important is the color, meant to mimic the earthy brown hue of air-cured burley tobacco, a nod to the crop that played a pivotal role in Durham’s growth after the Civil War.

“When I think of Durham, I think of sweet tea, biscuits and tobacco,” Gross says. “This is about a sense of pride for the city, its history and its beer.”

Bryan Roth is a North Carolina-based writer. Find him tweeting about beer at @bryandroth.

Boulevard Unfiltered Wheat Beer

ABV: 4.4% | American-Style Wheat BeerTasting Notes: Boulevard’s Unfiltered Wheat definitely brings back memories of traveling through the Midwest. This is such an eminently drinkable beer, and the wheat additions supply a huge amount of the overall character: delicate, husky toast; robust head retention; and bright cloudiness conjuring images of past wheat ales loved. Forget about clove and banana—this instead offers vibrant lemon custard and firm mineral bitterness. –Ken Weaver

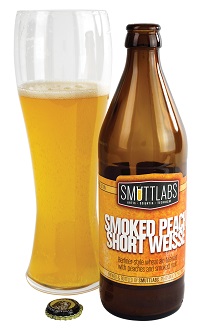

ABV: 6.9% | Berliner-Style Wheat Ale w/ Peaches & Smoked Malt

ABV: 6.9% | Berliner-Style Wheat Ale w/ Peaches & Smoked MaltTasting Notes: A fruited Berliner-style weisse far from both Florida and Berlin, adding smoked malt into the mix. If you stick with the belief that fruited Berliners should be built around the fruit, then you’ll want to give this one a try. Ripe peaches and a tingling acidity hover in the glass. Up front the beer is tart and puckering, but the sweet, ripe peach quickly joins the party mid-sip. The smoked malts combine with a higher-than-usual alcohol level to add a dimension and support the fruit. –Adam Harold

Cultural geography at its best!