Pumpkin Power: The Rise and Reign of Pumpkin Beer

In the past 25 years, pumpkin beer has gone from an experimental specialty beer to a seasonal phenomenon. Photo courtesy Elysian Brewing Co.

Take a stroll through just about any grocery store in America between late August and early November and the pervasiveness of pumpkin-flavored everything becomes apparent. There’s pumpkin spice coffee and tea, bagels, muffins and chips, air fresheners and candles—and that’s only a slice of the pumpkin pie-flavored market. Do a 360-degree spin in a beer store and the shelves and displays of pumpkin pie-inspired beer, imperial pumpkin ales, pumpkin stouts and porters and even shandies and ciders, all point to one thing: America loves pumpkin.

Of course, the question of whether we the people love pumpkin has never really been a question at all.

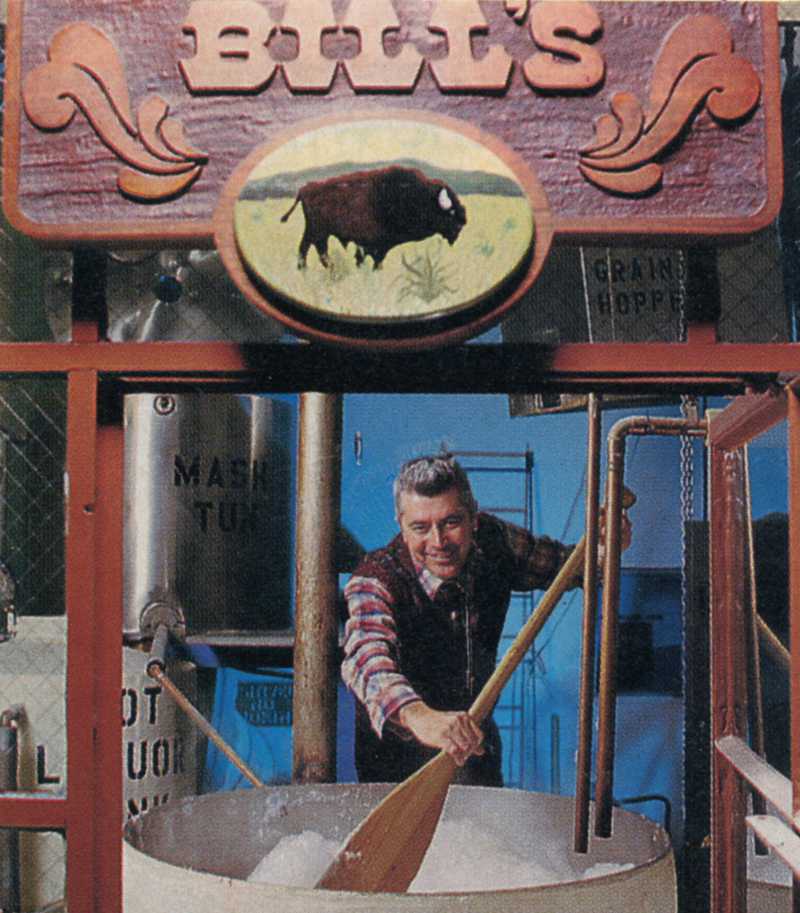

“The pumpkin thing is as American as apple pie. Pumpkin pie? Come on, that’s as American as you can possibly get,” says Bill Owens, founder of Buffalo Bill’s Brewery in Hayward, CA, and brewer of the first commercial pumpkin beer in the country. “When you have something that’s so culturally deep, everybody loves it.”

And in terms of beloved pumpkin spice-flavored foods, pumpkin beer is right up there with the Pumpkin Spice Latte. In the last 25 years or so, pumpkin beer has gone from an experimental specialty beer made by a handful of brewers to a seasonal phenomenon and a major force in the craft beer market. Its reign as seasonal beer king grows more extensive every year as pumpkin beer seeps into summer and arrives on shelves in the middle of July into August, to the ire of summer drinkers and the delight of eager pumpkin beer fans.

Pumpkin’s roots do run culturally deep, but the pumpkin itself was not always so glorified. Rather, it was respected as a utilitarian food source, explains Cindy Ott, author of the book Pumpkin: The Curious History of an American Icon.

“Pumpkin ale was not something that was treasured in any way, shape or form,” she says. “In the early Colonial era, pumpkin was cheap and prolific and grew like a weed. When there was no wheat for bread or sugar for cake or barley for beer, they could substitute the prolific pumpkin.”

Thus, pumpkins became known as a “last-resort” food and a crop that was associated with hard times—which is what helped fuel its climb to American icon. As Americans moved into cities in the early 19th century and the distance from their agrarian roots grew greater, their nostalgia for simpler times was projected onto the pumpkin, Ott argues. Other better-tasting squashes had greater market value and were incorporated into daily meals much like they are today, while the poorer-tasting pumpkin was left behind in the fields and often used as livestock fodder. The pumpkin became intertwined with ideas and associations greater than itself, of an old-fashioned way of life on the small family farm, nostalgia and tradition.

“Those ideas, about last resort and hard times and, ‘Throw the pumpkin in and take care of yourself and your family on your small plot of land,’ became symbols and stories of American survival,” says Ott. “It’s these kind of associations that people are buying, and the associations are really positive and affirming.”

We might not be consciously aching for our agrarian roots today, but the ideas surrounding the pumpkin are still overwhelmingly pleasing—images of rustic pumpkin patches with red barns and hay rides, toothy, glowing jack-o’-lanterns perched on stoops and a slice of pumpkin pie with a scoop of ice cream on top after a hearty Thanksgiving meal.

Seasonal Spice

While our associations with pumpkins may have changed, the pumpkin itself and its earthy, squashy, borderline bland flavor has not.

Enter the aromatic flavorings of pumpkin pie spices: cinnamon, ginger, cloves, allspice and nutmeg. This spice dream team has retained the positive associations of pumpkin, the harvest and changing seasons, while casting off the pumpkin itself. Take, for example, Starbucks’ enormously popular Pumpkin Spice Latte, which has become the poster child for the pumpkin craze of late and is not made with any real pumpkin.

It is the same conundrum that “Buffalo Bill” Owens ran into when he brewed the first pumpkin beer in 1985. Owens was inspired after reading about how George Washington brewed pumpkin beer, so he grew his own pumpkin, brought it down to the brewery, chopped it up, baked it in the pizza oven and added it to the mash tun, where the malt is mixed with hot water to convert complex starches into fermentable simple sugars.

There was just one issue with the beer, Owens says: “The only problem I had was at the very end was there was no pumpkin flavor whatsoever because you’re taking a starch, the gourd, converting it to sugar, fermenting the sugar, adding hops and then fermenting, so any flavor from the pumpkin is stripped away.”

To solve the problem, Owens walked over to his local market, bought a can of pumpkin pie spices, percolated it so he had a quart of pumpkin-flavored water, which he added that to the beer and then carbonated and bottled it.

“I was very proud of my secret ingredient, which came out of a can from the supermarket,” says Owens.

And voilà—the modern pumpkin beer was born.

Heather Vandenengel

Heather Vandenengel is a freelance beer journalist and news editor for All About Beer Magazine. She is based in Montreal, QC, but takes any excuse to travel, especially when it’s for beer.

Pumpkin beers come out in July now. A bit too early.

Beer producers are diluting the impact and tradition of seasonal beers by releasing them far too early into the retail market. By giving customers everything they desire the product becomes less desirable and eventually the demand will dwindle. Octoberfest and Pumpkin in July. Christmas in October. Spring in January and Summer in March. I am retailer and already have seen this downward trend happen to some seasonals.

@jb. I agree that Pumpkin beers in July is overkill. But unfortunately this is no different than any other industry, pushing their wares a season early (shorts in march anyone?).

@Michael Papacek. No disagreement there. Unfortunately large warehouse stores (e.g. BevMo, Costco, Total Wine, etc.) demand shelves with seasonals. So the only choice a brewery has is to commit when a pallet or more is on the line.

-My 2 cents.

This is not beer. Its crap. Cool ade. It’s a decline in the tradition of beer and ale. Even the multitude of India pale ales is crazy. How many hops can you add? Buds idea of beer o Rita ‘ s is another ridiculous trend. Call them something other than beer.

@Mike – I disagree the pumpkin beer is total crap, but that’s a matter of opinion and not “fact”. Your stance on IPA’s I actually agree with, but, alas, it is also an opinion. Cheers.

I read that there was no pumpkin in that first beer… Anyway it’s pumpkin pie beer, not pumpkin ale. Oh and most ‘pumpkin’ beers were probably brewed with what we would call winter squash. Even now pumpkin is a not-very-specific term – usually means a round squash! Most canned pumpkin is a winter squash that we would not now call a pumpkin. And saying it has no flavor is rediculous. I add roasted squash to beer and there is a very definite flavor, though perhaps not what most people would call pumpkin flavor (again that’s pumpkin pie), but there are roasted caramel notes, earthy, and it adds some sourness (not expected, but it does so each time).