There’s no doubt we are living in the golden age of American beer. The quality of beers available to today’s consumers, coupled with diversity in styles and flavors, is unparalleled. But I feel like we’re missing something: bona fide beer barons.

Oh sure, a few names have risen to beer nerd celebrity status. Dogfish Head’s Sam Calagione had his own reality TV show, and I bet hop heads have named their sons Vinnie after Russian River co-founder Cilurzo. But you won’t find a Grossman Field in Chico, California, and Boston will never rename Fenway Park after Samuel Adams founder Jim Koch.

Perhaps it’s for the best that today’s brewery owners spend their money procuring the best hops, not naming rights or sports sponsorships. If we look to the past, however, we’ll find beer barons still loom large in Milwaukee, St. Louis and Cincinnati. Visit these three cities to explore beer scenes past and present.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Frederick Miller, Joseph Schlitz, Valentin Blatz, and “Captain” Frederick Pabst were the German immigrants who put the Cream City (so named for its cream-colored bricks) on the beer map, but it was Jacob Best Sr. who opened the Empire Brewery here in 1844. Within 15 years there would be more than 30 in town, including a few with Best family connections. Jacob Jr. and his brother Phillip renamed Empire as Jacob Best Brewing. Later, when Phillip’s daughter married Frederick Pabst, that brewery would again change names in 1889. Similarly, Jacob Sr.’s other two sons—Charles and Lorenz—operated a nearby brewery called Plank Road, better known today as Miller (or, well, MillerCoors, but mergers and acquisitions are nothing new to this industry) you can visit all of them at the Forest Home Cemetery (2405 W. Forest Home Ave.). Among the beautifully laid out 200 acres with city founders and sausage kings galore, there’s a section coined the Beer Barons’ Corner. From the Blatz mausoleum to the outcropping of Pabst tombstones, whole brewing families rest eternally.

Fred Miller’s Plank Road Brewery c. 1870 (Photo courtesy MillerCoors Milwaukee Archives)

Visit in June and you can attend Brunch with the Beer Barons. The event, co-produced by the Milwaukee County Historical Society, features real-life descendants of the Blatz, Pabst and Gettelman families, plus reenactors. What’s for brunch? Brats, naturally! The Milwaukee Brat House (1013 N. Old World Third St.) features a long menu of creatively topped ones or the classic. At the Wisconsin Cheese Mart (1048 N. Old World Third St.) you’ll find fresh curds so squeaky it sounds like a game of racquetball in your mouth. The gift shop housed in an add-on to the Pabst Mansion (2000 W. Wisconsin Ave.) is actually the hall where Pabst won its gold medal (no, not a blue ribbon) at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

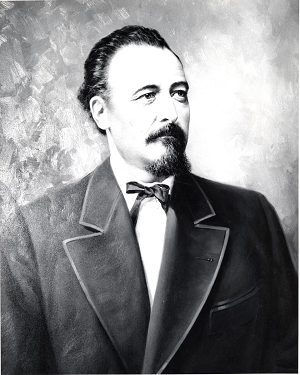

Fred J. Miller (Photo courtesy MillerCoors Milwaukee Archives)

Back in 1996, after Pabst powered down its brewing operation, the 20-acre, 10 million barrel capacity brewing campus became a veritable ghost town. Today, it’s becoming a bustling micro-hood thanks to Jim Haertel who saved the campus and now runs the Best Place at the Historic Pabst Brewery (901 W. Juneau Ave.). The name, of course, is a reference to Jacob Best and visits, replete with a PBR or pint of Pabst Andeker, include an entertaining tour and vintage Pabst TV spots. That Andeker, incidentally, is a helles lager that debuted in 1939 remembered mostly by Milwaukee old-timers. It’s now brewed next door at the new Pabst MKE Brewery (1037 W. Juneau Ave.), a stylish looking, ultra-modern brewpub that acts as a research-and-development pilot for Pabst.

Speaking of MKE (Milwaukee’s airport code and de facto abbreviation), Milwaukee Brewing Co. is constructing a new destination brewery. The company, founded in 1997 by new school beer baron Jim McCabe, began as the Milwaukee Ale House (233 N. Water St.), a 15-barrel brewpub along Milwaukee’s riverwalk. A decade later, the 50-barrel brewhouse at 613 S. 2nd St. was operating. With another decade under its “Milwaukee goiter,” the new MKE Brewery (1150 N. 9th St.) will occupy the 50,000-square-foot Pabst Building 42. The idea of playing cornhole, bocce or volleyball on the epic rooftop biergarten with a pint of O-Gii (the brewery’s tasty witbier with chamomile) or Louie’s Demise (its flagship amber ale) is too good to pass up.

Without leaving the Pabst compound, check into the Brewhouse Inn and Suites (1215 N. 10th St.) right around the corner. It’s where Visit Milwaukee accommodated me, and where beer travelers will find a centerpiece—centerpieces, really—of six shiny, copper kettles used ‘til the brewery shuttered.

The free tour at Miller Milwaukee Brewery (4251 W. State St.) details Frederick Miller’s journey to launching the brewery in 1855. From the cream brick buildings and lagering caves of old to the 7.5 million barrel behemoth it’s become, it’s a far cry from the quaint 10-barrel breweries most beer travelers experience. Then again, there is the pilot Miller Valley Brewery responsible for innovation. There’s always something new coming down the marketing pipes, such as the forthcoming Two Hats line of light, sessionable and fruit flavored beers.

Milwaukee’s nearly back to having 30 breweries, so there’s plenty more to explore beyond where lager-brewing German immigrants tread and brewed. The current crop of beer barons begins with Russ Klisch, a daily fixture at his Lakefront Brewery (1872 N. Commerce St.), established 1987. Riverwest Stein Amber Lager—characterized by burnt sugar and leather—washes down Lakefront’s to-die-for fried cheese curds. (To get even more Milwaukee, they host a Friday night fish fry with live polka.) Additionally, taste your way through an impressive glut of old-European styles (and neo-American sodas) at Sprecher (701 W. Glendale Ave.). In this town that light lagers built, the city’s original post-Pro craft brewery makes Black Bavarian, one of the finest schwarzbiers produced in America.

St. Louis, Missouri

It’s not only Budweiser that made St. Louis beer-famous. Jacque Marcellin Ceran deHault St. Vrain began brewing table beers and porters in 1810 at a brewery later known as the St. Louis Brewery (some 40 would call the city home in 1860). It boasted an underground beer garden and a bowling alley. (St. Louis used to be home to the Bowling Hall of Fame, itself part of the German influence.) Nowadays, the city’s most notorious baron(s) are Eberhard Anheuser and his son-in-law, Adolphus Busch. The brewery’s origins date to 1852 but received its hyphenated name in 1879. There are myriad tour options at the 142-acre Budweiser Brewery (12th and Lynch St.) and yes, most include seeing the Clydesdales. Choose from more than 50 family brands for your gratis beer in the hospitality bar afterwards.

Less than a mile south is the old Lemp Brewery Complex (3500 Lemp Ave.) It still looks like the huge brewing facility founded in 1864, but there’s no more Lemp. If you’re feeling dry, the nearest brewery is Earthbound Beer (2724 Cherokee St.). If you think St. Louis-style American lagers are old school, wait until you try Earthbound’s ancient-inspired Gruit out of Hell.

Though Fallstaff has fallen by the wayside, St. Louis is once again teeming with modern beer barons. Tom Schlafly co-founded the current iteration of the St. Louis Brewery (2100 Locust St.), producers of the Schlafly brands, in 1991 with a brewery—now the Tap Room—housed in a beautiful, old printing building. Perennial Artisan Ales (8125 Michigan Ave.)—one of the first and few breweries in St. Louis not named Anheuser-Busch to medal (repeatedly) at GABF—was founded in 2011 by Phil Wymore. Its Belgian-inspired ales are sought out worldwide but best enjoyed at their Tasting Room. And the city’s latest baron—who left Perennial to turn his side project into a full-time gig—is Side Project’s (7458 Manchester Rd.) Cory King. King’s wild ales are available at the brewery’s tasting room (open weekends only) or the Side Project Cellar (7373 Marietta Ave.) a block away. Visit in June to attend the St. Louis Brewers Heritage Festival and sample through more than 50 St. Louis-area breweries beneath the iconic Gateway Arch.

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati may not boast the heritage brands of cities like Milwaukee and St. Louis, but it was absolutely one of America’s primary landing spots for German immigrants—and their breweries. So massive was the population that one canal was nicknamed the Rhine for the river running through Western Germany’s Rhineland. The neighborhood, still known as Over-the-Rhine (OTR), supported Cincy Metro’s three dozen breweries named for 19th century beer barons John Kauffman, John Hauck, Ludwig Hudepohl and Christian Moerlein. Today, the Kauffman lagering caves beneath the defunct brewery’s malt house are part of the Brewing Heritage Trail. Source Cincinnati brought me out to explore the city’s historic and present beer cultures, which is how I got to enjoy some dark, bready Moerlein Emancipator Doppelbock during the annual Bockfest at what is now the Moerlein Brewery resuscitated by Cincy’s contemporary baron, Greg Hardman. The production brewery (1621 Moore St.), where Hardman is responsible for salvaging other local brands like Schoenling-Hudepohl Little King Cream Ale (in diminutive nip bottles) is in OTR. There’s also the swanky Moerlein Lager House (115 Joe Nuxhall Way), a brewpub on the banks of the Ohio River overlooking northern Kentucky.

While not part of the Brewing Heritage Trail, among the city’s 20-plus breweries is the original Schoenling Brewery, now the Samuel Adams Cincinnati Brewery (1625 Central Pkwy.) Boston Beer’s larger-than-life baron Jim Koch is actually a Cincy native. Tours are only offered during Zinzinnati, America’s largest Oktoberfest celebration.

Incidentally, the original Moerlein brewery has been repurposed as Rhinegeist (1910 Elm St.), which helped return the town to brewing prominence. Beyond the massive, rollicking event space and chill rooftop biergarten, beers like Truth IPA and taproom-only Uncle, a 3.8% British mild, make it a requisite visit. Other only-in-Cincy hotspots include OTR’s Taft’s Ale House (1429 Race St.) which, despite setting up inside the deconsecrated St. Paul’s Evangelical Church from 1850, the brewers flaunt anti-Reinheitsgebot beers like Nellie’s Key Lime Caribbean Ale and Liquid Advent, a chocolaty porter featuring cinnamon and chilies. Another St. Paul’s (Catholic) Church-turned-brewery is Urban Artifact (1660 Blue Rock St.) in the Northside neighborhood. The Thoroughbred Series boasts bourbon-barrel-aged beers inspired by cocktails like Mint Juleps and Moscow Mules, and the space doubles as a venue for special events. Even without family names on large halls, modern beermakers certainly continue to support the art.

Brian Yaeger is the author of Red, White, and Brew: An American Beer Odyssey and Oregon Breweries.

Thank you for the story and history lesson. More opportunities to put on my bucket list.

You mention Joseph Schlitz, almost in passing. Are there no memorials, fests or tributes to this giant of the industry? After all, Schlitz was once the largest selling beer in the World, whose motto was “The beer that made Milwaukee famous”, and then again outsold all the brewers of Chicago which had about twenty local brewers in that city.

I attribute one of the reasons for the rise of craft beers and micro-breweries almost directly to the demise of Schlitz. I remember what we were left with, watered beer labelled ‘lite’, alcohol infused sodas called ‘ malt liquor’, and the farcically named ‘ice-beer’. God bless Rolling Rock the sole salvation back then.