Drei Kronen is one of several German breweries with brewpubs in China.

Published in the November issue of All About Beer Magazine

It was with the master of ceremonies’ final costume change that the revelers were at their most enraptured. Those gathered at Beijing’s Paulaner Bräuhaus—whether German veterans of Oktoberfest or Chinese new to the world’s biggest booze-up—had never seen anything quite like it.

The aging entertainer had donned a Dickensian nightgown and cap, lighting his way through the gloaming in the giant marquee with a candleholder in hand. He stomped along the banquet table through diners’ sausage and sauerkraut remains, belting out a raucous Bavarian drinking song backed by the oompah band. His hairy, stout calves were bared to the world, and Chinese ladies blushed at the occasional glimpse of his oversized bloomers.

With busty lederhosen-clad dancers on the stage barely challenging for anyone’s attention, our main act neared the end of his song. And then came the party trick. He opened his mouth wide enough to swallow a whole pork knuckle and in went the candle, extinguishing the flame. The crowd went wild, and the large sums most had paid to be at the opening of this venue’s 2010 Oktoberfest seemed more than worth it.

Similar scenes play out every fall at the Paulaner Bräuhaus in Beijing, where Oktoberfest is big business. But it is far from alone in selling the beer, food and drinking culture of Germany to the Chinese. While the capital’s outpost of Paulaner can be credited with starting the popularization of German brewpubs in mainland China after opening in 1992, a swath of such places has followed, in Beijing and most first- and second-tier cities.

Cultural Phenomenon

Premium-priced helles and weissbier have huge appeal in China. A one-liter stein sells for about 60 yuan (about 9.80 U.S. dollars) in most brauhauses in Beijing, which has China’s highest minimum hourly wage of 15.2 yuan. For the country’s growing number of nouveau riche, clinking and downing steins of this stuff with their guests holds just as significant a role as it would have for the hosts of a beer hall-set putsch in Germany. Look at me, most Chinese drinkers are saying, I have cosmopolitan tastes and money to indulge them, and inviting my tablemates to join me at this lavish party shows my respect for them‚ tremendously important in a country obsessed with establishing and maintaining “face.”

Fast-forward to the 2012 Paulaner Oktoberfest in Beijing, and this dynamic seemed to have been diluted, however. The launch night was noticeably less bombastic. There was the customary tapping of the festival’s first keg. The sponsors spoke a few words. Guests enjoyed their food and several beers brewed onsite. But it was hard to deny that the knees-up was muted compared with previous outings.

Not only was the financial crisis to blame, but the continued quietening of Beijing brauhauses since then also comes against the backdrop of a major campaign by the Chinese government against “extravagance.” The tit-for-tat banquets and gift giving that have greased the wheels of China for dynasties have come to be considered profligate. Yes, new President Xi Jinping is targeting exactly the kind of ostentatious Chinese souls, whether local officials or deal-clinching businessmen, who love German-style restaurants. With the campaign still dominating the front pages of Communist mouthpieces, it seems highly likely that 2013 Oktoberfest parties will be blown by these sociopolitical winds. While none of the big venues are set to cancel their fall events, they are sure to be slightly more restrained than usual.

There are also signs that German beer is losing its voguish popularity among Chinese, who are instead developing more of a taste for American imports. Importers and specialist bottle shops point to Chinese looking for something new. After a period when German and domestic beer was all that was available, punters are expanding their horizons to the more diverse styles offered by the New World. Germany may have superior prestige, but it faces challenges from new pretenders.

So how did we get to this stage? And what are brauhauses here doing to keep their place?

]]>During the nine months that the brewery survived, I came to meet new people and develop relationships that remain with me today. It’s those friendships that make the industry of craft beer as strong as it is. Collectively, we share a passion for making amazing liquid, and oftentimes this enthusiasm manifests itself in collaborative efforts between like-minded brewers.

This notion of brewers getting together and sharing ideas on recipe development would actually appear to be a recent phenomenon. Last time I checked, the guys making Budweiser and Coors Banquet Beer haven’t convened annually in the hopes of creating the ultimate lawn mower lager. In their defense, they may be waiting for hell to freeze over. That would appear to be the ultimate reason for the mountains to turn from blue to red.

Each brewer has his or her reasons for working on a collaborative project. When I approach these opportunities, I’m drawn to them like musicians sharing a love for sitting in and riffing through a part of someone else’s jam session. I rarely look to be the lead on the project and prefer to be a traveling artist collaborating at someone else’s facility so I can see how things are done outside our environment.

I’ve collaborated on over 15 different beers now with friends, acquaintances and even people I’d never met before. Each of those productions has given me a chance to explore other breweries, foster new friendships and create awareness for our brands. Traveling to other corners of the globe to brew a new recipe continues to be one of my favorite parts of my job (especially if that travel takes me to Maui, as it did last winter).

There isn’t a published set of rules for collaborating on beers, but there are a few things I consider before agreeing to make bedfellows with another brewery. First and foremost, I believe with conviction there needs to be a legitimate reason for collaborating. Without this, you have no story, and interest in the project will be tepid at best.

During a judging session at the 2007 Great American Beer Festival, while seated next to Hildegard van Ostaden of Brouwerij Leyerth (Urthel), she and I hatched a plan to collaborate on a low-alcohol saison under The Lost Abbey brand. We knew in nine months San Diego would play host to the Craft Brewers Conference. As such, many of the best brewers in the world would be visiting (including Hildegard) and looking to experience our brewing culture. She came to our brewery armed with a wealth of brewing knowledge I have never possessed. Spending eight hours working on a brew together allowed us to converse in depth on some ideas I wished to inquire about.

The recipe was quite simple to work out. Hildegard hoped to brew a saison with no spices in a straightforward manner. Given that The Lost Abbey produces Red Barn Ale (a spiced saison) year-round, this was a great side project for the brewery. Her husband, Bas, created the artwork that adorned the label. We call it the Dom DeLuise label here at the brewery, as Bas really played up my strongest features …

Ten years ago, collaborative beers were less commonplace than they are today. The landscape has changed, and the shelves are now littered with these kinds of releases, I’m left wondering if we have hit a proverbial wall in an almost Grammy-fication of collaborative beers.

Each year, we know that the Grammy Awards show will feature a night of artistry and even some unconventional unions of musicians. Some will seem incredibly natural, like Santana and Rob Thomas, and others more fraught with peril (Milli Vanilli anyone)? While not my first Grammy Awards show memory, I clearly remember that February night in 2001 when Marshall Mathers (Eminem) took to a thundering and rainy stage to perform a version of his hit “Stan.”

He was joined that night by Sir Elton John, who accompanied Eminem in a show of unity. As an openly gay male, John sat in to debunk the rumors of hate swirling around The Marshall Mathers LP release. Their duo still rings as one of the best collaborative musical performances I have ever seen. But most importantly, their performance mattered. It resonated and it found legacy. To me, the essence of a great collaboration should also cause a group of people to work together, hopefully finding meaning in a shared experience, all the while creating an exceptional opportunity for the audience.

And while I’ve been around the collaborative brewing block once or twice even in Belgium, I’m no brewing moped. Rather, I prefer to believe I’ve become a seasoned and selective partner who knows what he is looking for. Of course, we all have to start somewhere. For me, the year was 2002, and like many I was a young ambitious brewer when I collaborated on my first beer. Some local brewer friends and I got together to brew a German-style stein beer. This method of using super-hot rocks to heat the wort was a first in San Diego and certainly told a great story.

Some seven years later, I built on that same process and improved it when I invited Tonya Cornett (then of Bend Brewing Co.) to collaborate with Port Brewing Co. on a new spring release named Hot Rocks Lager. In launching Hot Rocks Lager, we were able to bring back the super-heating of black granite rock addition to a batch of beer and retell the story of how the process came to be. Our brewers love this beer, and the process of super-heating rocks and caramelizing wort continues to be one of the most interesting things we do here at the brewery.

Tonya and I divided the recipe in half. She was tasked with creating the grain bill as I worked on the hops and tweaked the fermentation to take advantage of my understanding of our brewery processes. In doing so, we brought together a shared idealism, and the resulting beer has become one of our most award-winning recipes (a lager no less). If you’re keeping score at home, that’s one for Collaborations and zero for the Duds.

The role of collaboration is complicated. Sometimes it’s educational. Often, it can be technical if a smaller brewery works with a larger, more sophisticated brewery. It can be celebratory or even improvisational. There are few rules for collaborative brewing, but singularly the one that guides me is that too many cooks in the kitchen can yield less than ideal results. This happened to me and some of my best brewing friends once in Chico, CA.

A group of us worked to produce a heritage lager in a sort of “Esprit de Saint Louis” sort of way. It featured wild rice, purple potatoes and even some “beachwood” collected from both the shores of Delaware and San Diego. All told, the beer turned out fantastic. Yet it really didn’t “do” anything.

So we were ushered to a super-secret lab where we played around with all kinds of concentrates and natural additives. Ultimately some carrot juice and cucumber essence jumped in to support the lager. As we set out to improve the beer, the cooks in the kitchen crossed our fruit and vegetable streams in a disastrous those-ingredients-are-better-left-for-salad kind of way. With apologies to Stevie Wonder, I learned that unlike ebony and ivory, cucumbers and carrots do not always go together forever in perfect harmony …

Thankfully, there are more successes than misses, and collaborative beers are here to stay. They present the consumer with amazing opportunities at every turn. What remains to be seen is how many duds the shelves can support before there is a rejection of the artistry. I know that we’re not done with our collaborations here at the brewery, and we’ll continue to be selective about whom we partner with and hope the rest of our craft brewer brothers and sisters follow an equally rooted example.

]]>

Chad Campbell and Brett McCrea of 16 Mile Brewery

Brett McCrea and Chad Campbell founded 16 Mile Brewery in 2009 in Georgetown, DE, a town in the geographic center of the state said to be 16 miles from anywhere. The brewery is sited in a 120 year-old barn on land owned by McCrea’s family.

AAB: This has been a homecoming for both of you.

BMc: That’s correct. Basically, I grew up in a house that’s 300 yards from here. I went to undergraduate in Maryland, and graduate school at the University of Pittsburgh. After that, I worked for the federal government for 10 years. I moved back to help my father. Chad also grew up in Georgetown, but I didn’t really know him: we went to the same high school and the same college, although he likes to remind me that I am precisely four years older than he is!

I assume you have to remind him, then, that he was the one looking up to you.

BMc: I’ve never said that, but now I will! We wanted to open up a business in our hometown, because, if you had to put a melting pot together, it’s unique. It’s very small, but arguably the third most powerful court in the United States is a mile up the street.

Really? What is it?

BMc: It’s the Court of Chancery. If you look them up, a lot of the Fortune 500 are incorporated in Delaware, so a lot of the business court decisions are made here. Michael Eisner got sued here, things like that. So there’s prominent judges there, chancellors and vice chancellors. Some of them come here to have a drink, sitting next to dirt farmers. It’s a unique mix of people who come through.

I noticed your connection to Georgetown plays out in the names of your beers.

BMc: To be honest, this company really sucks at naming things. It took an act of God to come up with the name of the brewery. The name 16 Mile is a localism, because Georgetown is said to be 16 miles from anywhere. The town was formed after farmers from the western part of the county petitioned the general assembly to move the county seat from Lewes to somewhere more central. There’s a circle in the middle of Georgetown, and they took an azimuth from there and drew a big circle, and so it would be roughly 16 miles—about a day’s horse ride—from anyplace in the county. That’s how we got the name of the brewery.

Our beers are mostly named for state or local icons. If you look on the label of Blues’ Golden Ale, you’ll see the Delaware Blues Revolutionary War Regiment. It’s a very proud history: they fought in every major battle. They were decimated, because they were known for close-in fighting. That statute on the label is in front of the Legislative Hall in Dover.

Another one is Amber Sun, an amber ale named after our sunsets. There’s really only one place you can see sunset over water in Delaware, and it’s at the Breakwater Lewes Lighthouse.

Old Court is named for the original courthouse in Georgetown. We’re real proud of it, because that’s the beer that made Roger Protz’ new book 300 More Beers to Try Before You Die.

We have nearly 2,400 breweries in this country. How will 16 Mile stand out?

BMc: It’s the reintroduction of the session-based beer. The craft industry by and large has been almost a reflexive movement away from the national brands, understandably so. The further away from them they could get, the better. What you saw was a lot of high-alcohol, highly hopped beers. I’m not knocking anybody, but if you look at the top 50 beers on BeerAdvocate, very few of them are below 7 percent alcohol. There’s this notion that to be the greatest, there has to be an extreme associated with it.

I’ve lived in England and Germany, and Czechoslovakia (when there was one), and Belgium—places where they make good beer. I’ve always had an affinity for English beers because they do so much with low alcohol. We do English-style beers with an American craft twist, so there’s a bit more alcohol than a traditional English beer.

I feel the pendulum is swinging back to session, with a lot of indications in the market. Pete Slosberg, one of the founders of the craft beer movement, opened up Mavericks [line of beers], and most of the beers in their portfolio are below 4 percent alcohol. You’re starting to see the industry titans shifting, and I think that’s where the future of beer is. We feel it’s the simplicity of what we do that makes it great.

I understand you have an unusual collaboration with an English brewery.

BMc: That’s right, our Heraldry series with Copper Dragon in Yorkshire. We came up with this notion of a collaboration with an English brewer, based on events in English history. We started building beers around the stories.

The first one we came up with was the Waterloo brew. We took elements of that battle, and combined it into a beer. To reflect Wellington, we made an 8 percent strong English golden, along the lines of Golden Pride from Fullers. We took hops from the area the Prussian soldiers came from. We took a yeast strain from Belgium to represent Waterloo. Then for the coup de grâce, if you will, we took toasted French oak and soaked it in a case of Napoleon brandy, and put it all together. It came out very well.

What’s the process of collaboration?

BMc: We largely Skype with them. There’s a renaissance in England in craft beer, and what we do is bring the American component to their beers. They wanted to do a beer for Saint George, the patron saint of England. You know on the British flag, the cross in the middle is red? They asked us “We know you do an amber beer. Would you mind giving us the recipe?” They made it and released it in England.

And for us, the real coup, they gave us a recipe for Russian imperial stout with a pedigree back to the time of Catherine the Great. It’s a powerful beer.

That beer will be the base of the next Heraldry beer, which will be the meeting at Yalta. FDR was a big fan of bourbon, so we’re going to soak humidor-quality wood in bourbon, to signify Churchill’s cigar. Then, we may end up using an English hop—although Russian imperial stout is already an English beer.

We just released Made in the Shade, after the Scottish Black Watch, a very famous military unit in Scotland. We made a black IPA, we called it Made in the Shade, because they largely served in the shadow of the British Army, and we added English oak soaked in a case of 12 year-old Scotch.

The beers have been very well received. We don’t pilot-brew them, but we have a beer infusion tube that we’re able to use to test the combination of ingredients before we commit to a large batch. We’ve been working with BeerTubes.com to make a small infusion unit. We can suspend a small mesh bag that infuses an ingredient we want to test.

So you can avoid elements that might be jarring.

BMc: Everybody thinks, hey, bacon’s fantastic. Try it in beer. And this other notion, hey, what about Old Bay in beer? Naw, it’s horrible. So the infusion can solve a lot of misconceptions over what should be in beer. It’s how we can prototype these things.

We bring the idea of American experimentation with flavors, which you’re seeing a little in Britain. It’s a way we can use our experiences to assist them as they adapt to their market. Similarly, they give us insights into the tradition they have.

So you’re never brewing together at the same site. Your collaboration is information.

BMc: Right. All Skype and email on what we do and how we do things. Europe isn’t built on the collaborative traditions of American craft beer. Bringing that part of our tradition is something I believe will benefit everyone.

I understand you do have a restaurant, too.

BMc: We have a tavern here, but we have a new partnership in a restaurant called the 16 Mile Taphouse in Newark, DE. This particular location was the old Stone Balloon, which, since it’s right near the University of Delaware, has a legendary status. It was very well known in the eighties. Major heavyweight acts like Bruce Springsteen would come to this place. It wasn’t a matter of who had played at the Stone Balloon, it was who had not.

In addition to the Heraldry series, do you have other limited edition beers?

BMc: We do Collaboration Brews for a Good Cause. Delaware’s blessed with a solid cadre of chefs, some of which are James Beard finalists. Some have formed associations, like the Rehoboth Inspired Chefs Initiative. Those guys come in and we make beer with them and donate to their charities.

It used to be that wine bars were kind of the beginning of the wine evolution in the United States, and now it’s mainstreamed itself into restaurants. Beer is very similar. Beer started with outstanding beer bars like Blind Tiger or Monk’s, and what’s beginning to happen is craft is evolving into the mainstream of restaurants. We see restaurants as a critical component to the acceptance of craft beer.

We come from this area, and we try to celebrate that. If we’re blessed enough to sell all the beer in this area, we’ll be happy and content to stay where we are.

]]>

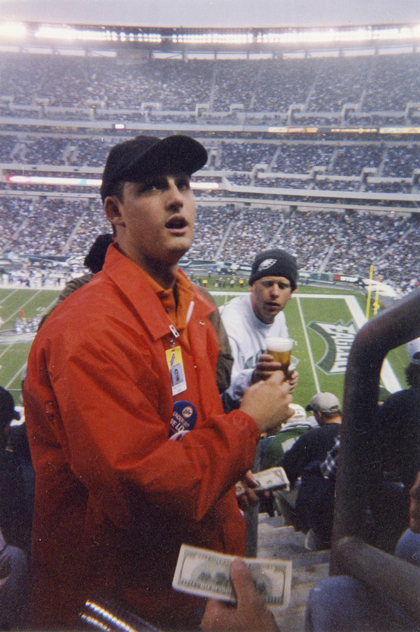

In 2004, Marc Cappelletti took a job as a Philadelphia Eagles Beer Man. Photo courtesy Marc Cappelletti.

By Marc Cappelletti

Growing up in a family with three Heisman Trophy winners and NFL running backs (John Cappelletti and, through marriage, Alan Ameche and Glenn Davis), I never had to go far for my football fix. Games, memorabilia, awards banquets—I was blessed to have intimate access to a sport I loved. But it wasn’t until I left those privileges at the front gate and strapped two cases of beer around my neck that I learned what it really means to be a part of the football experience.

It was late summer 2004. I was a year out of college and, after a short stint in the travel industry, had moved home to Philadelphia with a blank calendar and some souvenirs. At the same time, my favorite team, the Eagles, were poised to win the NFC East and, some were saying, the Super Bowl. I wanted in on the action. My first instinct was to apply for a marketing job and hope for game-time perks, but the team wasn’t hiring. I considered going the George Plimpton route and asking to be the team’s last-string quarterback, but an acute fear of having my legs broken by 300-pound linemen prevented me from even making the call. Then a friend told me about another way in. It involved barley, water, hops and lots of sweat.

This was the era before craft brews hit the stadiums, so the only choices were Budweiser, Bud Light, Coors Light and Miller Lite, the canned kings of sports arenas nationwide. Because Philadelphia fans have shown a tendency to throw things in the stands (batteries, snowballs, bottles, tantrums), every beer had to be poured into a plastic cup—a seemingly simple task. But while trudging up and down the aisles, stopping only to kneel amongst puddles of dip spit and the remains of peanut shells as 65,000 beer-thirsty fans scream in unison, “Hey! Beer Man! Gimme two!” pouring those 16-ounce tallboys is not so simple.

During the first game, perched high atop the upper deck (or the Nest of Death, as diehard fans call it), I fell victim to the wrath of carbonation three times. The frothy head spilled over the rim of the cup and onto the concrete steps below.

“Hey! Beer Man!” a nearby fan yelled.

I expected to hear how many beers he wanted.

“You suck!” he said.

I most definitely did suck. But over the course of the game and throughout the season I learned from my mistakes. I learned to respect the beer, to slow down, making sure that each pour was perfect. Tips increased. I learned that real Beer Men don’t just offer beer; they also sell it with phrases like, “The more you drink the better they play!” peppered in with the traditional, “Beer here! Ice cold!” When temperatures dropped, avoiding the term “ice cold” altogether is sometimes best.

The Beer Men set the tone in the stands and, if done with the right amount of panache, the fans respond in kind. They want to buy from a guy who is quick, competent, but who adds a little something to their experience—someone they’d want sitting next to them. Even in the Nest of Death a good smile goes a long way.

For once, beer got me off the couch. I showed up early for games to hang out with the other vendors: from the 18-year-olds out for some spending money to the pros who sold for all sporting events and concerts, or the guys for which selling beer was their second or third job. I gained a tremendous amount of respect for all of them and their backbreaking work.

By the end of the season, when the fireworks went off and Eagles won their first NFC Championship in 24 years, I had sold more beer, had more fun and connected with more fans than I had ever imagined. A few times I was even the focus of a full section “Beer Man!” chant. I was filled with pride, barely able to control my emotions, running around, high fiving strangers and jumping up and down as if I’d scored the winning touchdown myself. I even hugged a security guard.

As I have moved on to other jobs, the résumé bullet point about being a Philadelphia Eagles Beer Man has been the most commented on. I always smile when it is mentioned and embrace the irony that even when the discussion should be about my “actual” employment history, people really just want to talk about selling beer. Then I’m back in 2004, a humble servant of the fans shouting throughout the stands and into the heavens, “Let there be beer. And let it be ice cold.” Tips are appreciated.

Would you like to submit your story for consideration? Please email [email protected], and we will provide you with our guidelines.

]]>

North Dakota

For Trekkies, space is the final frontier. For nerds of another flavor—beer geeks—there’s always somewhere new to explore, some vast area of beer to pioneer if only on a personal level. With a rapidly growing number of hubs that vie for the title of Beer Town, USA, what about places not yet steeped in suds? Imagine being the Lewis or Clark of a new ale trail, or swapping a growler for a coonskin cap as the Davy Crockett of the last remaining frontiers in American beer.

No one’s ever said, “Let’s go on a beercation to North Dakota!” In early 2012 North Dakotans were the only ones without a home state brewery! Now there are five active breweries, and soon that may double. Down in Alabama, the Tide has turned and they’ve joined the rest of the union in legalizing homebrewing, which is sure to be a boon to upstart breweries. And in Alaska, the true last American frontier, Anchorage has long developed a beer scene, so it’s time Juneau is added to the list.

North Dakota

The Flickertail State has the dubious honor of being the least-visited state in the nation. Freezing winters. Flat year-round. Unless you’re visiting Saskatchewan or Manitoba, you don’t even drive through it. But at last, there’s beer. The format of this column usually focuses on a city or region, but for this budding brew spot, we’re looking at the whole state.

West in Medora there’s the Theodore Roosevelt National Park with the cabin Teddy lived in before he became president. The park features cool badlands (but it’s no Badlands National Park in South Dakota). The park ushers in fewer than half a million people annually, roughly the same crowd Disneyland welcomes over a week or so. If we’re being honest, more famous is Fargo, simply for being the title of the Coen Brothers film that made death by wood chipper a concept.

It’s one of the three states I’ve yet to visit, but with brewing activity it’s now the top of my list. For beer guides, I enlisted Tom Roan and Nancy Bowser, members of the excellently named Prairie Homebrewing Companions (at least to fans of Garrison Keillor’s “A Prairie Home Companion”). The Fargo club, founded in 1990, is the largest and oldest in the state (there are clubs in Dickinson, Bismarck and Grand Forks, too) and puts on annual events including Hoppy Halloween (HoppyHalloween.com). I was on a tasting panel to determine the best flagship beer from each state’s largest independent brewery, and noting North Dakota didn’t have one at the time, I reached out to the club to solicit authentic ale from the northern Great Plains. Tom and Nancy entered an American barley wine, putting most entries at a disadvantage in the blind tasting—and won.

Bismarck, the state capital located near the middle along I-94 with a population of just over 100,000 for the greater metro area, now holds a worthy claim to fame. It’s home to three breweries, including the first of the current operators to open, Edwinton Brewing Co. For a brief year before the name changed to Bismarck in 1873, the town was called Edwinton. I think the brewery’s founders, the Nelson family (brothers Brent and David, sister Kristen and father Dave) picked a great name. This Belgian-style nanobrewery introduced two beers in late 2012—Dæsy Saison and Lou Belgian IPA.

The newest brewery is Buffalo Commons Brewing Co., which opened in spring 2013 in Mandan, part of Bismarck Metro. You’ll find its Salem Sue Stout and Hoppy Trails Pale Ale along with Edwinton’s beers at Peacock Alley (422 E. Main Ave., Bismarck) offered in a BAM (big-ass-mug) among its regionally oriented beer menu with 23 taps. You’ll also find them at Reza’s Pitch (304 E. Front Ave., Bismarck). Where Peacock Alley is casual fine dining where you can pair craft beer with great steaks, Reza’s is a soccer-themed burger joint, so you can’t go wrong either way. Another great beer spot in Bismarck is The Walrus Restaurant (1136 N. 3rd St.), boasting over 40 rotating taps and “excellent” burgers and sammies.

Bismarck’s third brewery is a pub, Laughing Sun Brewing Co. (107 N. 5th St.). Roan points out this “very nice place” was started by a homebrewer active in the Muddy River Mashers. But co-founder Mike Frohlich is more than that. He brewed professionally at Rattlesnake Creek Brewery, a defunct brewpub up in Dickinson back in the ’90s. Some of the beers coming off Frohlich’s 3.5-barrel system include Feast Like a Sultan IPA, Hammerhead Red ESB and, depending on the season, Sinister Pear Belgian Golden Strong Ale or Black “Eye” PA, among others. Espousing the idea of supporting local, you’ll find artwork by local artists on the walls and bands, poets and writers on the mic.

It bears mentioning that some of the top spots Roan and Bowser recommend are North Dakota institutions with multiple locations around the state. JL Beers is a “small but popular beer and burger bar” that’s opened four (of its six) locations across the state starting with downtown Fargo (518 1st Ave. N., downtown). There’s also one six miles away in West Fargo (810 13th Ave. East), and you’ll find 30 taps spanning the style spectrum from around the country.

The real draw for Fargo as far as beer is soon to be Fargo Brewing Co. (610 N. University Dr.), which is currently contracting beer from a Wisconsin brewery, but the brewery and taproom construction are nearly complete. Brothers Chris and John Anderson, Jared Hardy, and Aaron Hill are the four co-owners, all native North Dakotans, with Chris serving as brewmaster, having honed his chops at Ice Harbor Brewing in the Northwest. Look for five core beers—Stone’s Throw Scottish Ale, a porter, a pale ale, a Kölsch-style, and the guaranteed favorite, Wood Chipper IPA—of which perhaps three will debut in cans, seeing as they’ve already procured the canning line. And they’re looking to brew a dozen or so seasonals on top. As for terroir, it should be noted that they’re getting malt from Rahr Malting in neighboring Minnesota, and even then they source much of their barley from North Dakota.

You’re sure to find Fargo on tap at Sidestreet Grille & Pub (301 3rd Ave. N.), “the original craft tap bar in downtown” with 27 taps and some 60 bottled beers. For a sports bar with even more pool tables, a 15-minute drive away is Fargo Billiards & Gastropub (3234 43rd St. S.), not only boasting predominantly craft taps, but also a billiard parlor with 56 tables.

As far as where to rest up during this pioneering beercation, check into the Hotel Donaldson (101 Broadway), where each of the 17 rooms is inspired by local artists. What’s more, this downtown hotel features the HoDo Lounge, primarily a martini/cocktail venue that taps six craft-only beers to be enjoyed listening to live music, or pop up to the rooftop Sky Prairie Lounge.

Speaking of rooftop lounges, don’t forget that there’s life between the I-94 corridor and Canada. Due north of Fargo in Grand Forks is the original of three Rhombus Guys Pizza locations (312 Kittson Ave.) also found in Fargo and Mentor. Perfectly complementing its craft offerings is a monstrous list of specialty pizzas, starting with T-Rex, crowned best pizza in Grand Forks from 2007-2011. The pie features pepperoni, sausage, Canadian bacon and ground beef, perfectly named for the carnivore whose fossils collectors used to flock to North Dakota to unearth. Save room for the S’mores pizza.

Over in Minot, one of the country’s newest and smallest breweries is Souris River Brewing (32 3rd St. NE), brewing a single barrel at a time, which explains why of its nine recipes, you’re only apt to find around three at a time. The brewpub takes care to serve locally sourced beef and bison, and don’t miss the baked fries. Don’t leave town without checking out the Blue Rider (118 1st St. SE), a quirky dive bar with a few craft taps that was started by cowboy artist Walter Piehl, who was clearly influenced by Der Blaue Reiter (the Blue Rider) German expressionist movement, for all you Kandinsky fans.

]]>

One of the greatest things about the craft beer renaissance is the almost endless variety of beers that are available in bars, restaurants, supermarkets, and liquor stores around the country. In most forward-thinking establishments, the choices of flavors and brands and styles is dizzying. It is a testament to the ability of the industry to adapt to what beer drinkers want today. It is also—for the industry—a royal pain in the ass.

Within the industry, the explosion of new brands and packages is called “SKU-mageddon.” Here’s why: The beer industry consists of the three-tier system: brewer, distributor and retailer. For all three, it is remarkably simpler and cheaper to brew, package, ship and retail 100 cases of Bud Light 12-pack cans than it is to ship 25 cases of Bud Light 12-packs, 25 cases of Blue Moon 12-packs, 25 cases of Fat Tire 12-packs and 25 cases of Corona 12-packs. That’s a vastly simplified example. Multiply that times 100 and you get my drift.

And the vast acceleration of SKUs is not the only change in the industry. We have gone from an industry of 4,000 distributors and 100 breweries selling 100 million barrels a year to an industry of 1,000 distributors and over 2,500 breweries selling over 200 million barrels (a barrel is the equivalent of two kegs, or 31 gallons). The top five brewers and importers currently sell over 90 percent of industry volume. The remaining 2,500-plus brewers share 10 percent. We have gone from a very limited number of SKUs to over 8,400. Meanwhile, as large grocery chains and big-box centers like Wal-Mart and Costco gain more and more of the nation’s grocery sales, we’re seeing a reduction in the number of independent outlets as well as a reduction in the number of bars.

So to reiterate: Many more breweries, many more brands and packages, selling much more volume of beer, through fewer distributors to fewer but larger retail outlets. Within that structure, we’re seeing more brewers coming out with more packages—craft brewers adding more brewing capacity like crazy as well as an average of one new brewery opening every day—but we’re not seeing the supermarket chains expand refrigerated shelf space at anywhere near the same rate. However, on the bar and restaurant side, we are seeing them add draft tap handles furiously to keep up with (and possibly exceed) the growth in keg varieties offered.

And then you have distribution. Distributors are mostly independently owned businesses that have been consolidating over the last 20 years and continuing to this day. There’s a common perception in the craft beer community that distribution capacity has not kept up with the pace of new craft brewers and brands. However, from where I sit, that simply does not reflect reality. As distributors have grown, they have become more technologically adept at being able to handle the tsunami of new SKUs. In addition, several craft-only niche distributors have popped up in certain markets to take up the slack.

Consider that one of the country’s largest beer distributors, Houston-based Silver Eagle Distributors, handled 400 SKUs five years ago. Today, the company handles over 1,300 SKUs among eight different distribution centers and is adding more every day.

As I mentioned before, one of the major bottlenecks in getting all those delicious brews into the consumers’ hands is the limited refrigerated shelf space in supermarkets and convenience stores. Thanks to Einstein’s law, two objects cannot occupy the same space at the same time, more’s the pity, so something has to give. And remember, keeping all the beer on the shelf fresh and rotated is an additional challenge.

Some retailers have opted to place slower-moving craft brands on the warm shelf, like red wine. The problem with that is many craft brands are unpasteurized, and storing them in ambient temperatures for any length of time can alter the taste of the beer, and not for the positive.

On the bar and restaurant side, we have the opposite problem. Many establishments have added so many draft taps—20, 50, 100 taps in one establishment is now not uncommon—that it becomes almost impossible to keep the beers that fill those taps fresh. And don’t get me started on keeping the lines clean. And in draft beer, it’s nearly all unpasteurized. Data firm GuestMetrics recently issued a report that while the number of craft beer brands sold in bars and restaurants grew about 22 percent in the first quarter 2013, craft beer volume grew only about 5 percent. In other words, we’re selling less beer per brand, which means less beer flowing per tap. That’s great for diversity and choice, but could be a red flag for beer quality on tap if the volume falls below a threshold.

“While we don’t necessarily see a shake-out in the near term, looking out at the next three to five years, the question will be the sustainability of the economics of a lot of the new entrants given the declining volume per available brand,” writes Bill Pecoriello of GuestMetrics.

It’s not just the explosion of new brewers and brands coming down the pike to watch out for, but also the amount of brewing capacity that is being built. You may have read about Sierra Nevada Brewing Co., New Belgium Brewing Co. and Oskar Blues Brewery building new breweries in Asheville, NC. Or Lagunitas building a new brewery in Chicago. Those are just the tip of the iceberg. Hundreds of other smaller breweries are a-building and expanding brewing capacity at a furious pace, not to mention the number of new breweries being built and coming online nearly every day.

If you slept through your Economics 101 class in college, here’s the one thing you need to know about excess manufacturing capacity in any industry with high fixed costs (like the beer industry): When demand doesn’t keep up with the building of manufacturing capacity, you end up with oversupply, and prices fall. You may say, “Hey, that’s a good thing.” But in the long term, it means many breweries will start losing money. The result is a flood of bad or old beer showing up in the market. It happened in 1998. Will it happen again? It all depends on whether beer demand keeps up with the fast pace of supply creating.

But hey, let’s not end on a sour note. The facts as they are today suggest that, yes, consumer demand for local, tasty, hand-crafted beer will meet or exceed supply. So far, so good. But the jury is out for 2014 and 2015.

]]>

Maria Scarpello and Brian Devine have driven to more than 300 breweries aboard their RV. Photo courtesy of Maria Scarpello.

By Gerard Walen

Ben and Karen Willmore experienced their first earthquake while in the parking lot of Stone Brewing Co. in Escondido, CA. Though not a major temblor, it shook enough to make cautious patrons move away from the alarming vibration of the massive glass doors in the brewery.

But the Willmores had no reason to go home and check for any damage. They were already home, relaxing in the recreational vehicle that has been their primary residence for several years. And they were at Stone because craft breweries sit high on their list of destinations for a life lived on the road.

They represent a subset of crossed cultures—a figurative marriage of craft beer fandom and nomadism. They are not alone. These craft beer nomads live and travel while visiting some of the nation’s more than 2,500 breweries, not to mention forays into Canada. In RV vernacular, they’re called “full-timers.” In craft-beer speak, they’re known as the common “beer geek.”

Maria Scarpello and Brian Devine started their quest in August 2010, from Lawrence, KS, traveling in their 19-foot 1999 Jayco RV, dubbed “Stanley.” They didn’t plan to make brewery visits a focus when they started, but after a visit to the first, Bristol Brewing Co. in Colorado Springs—and about 20 more before leaving Colorado—it became a primary focus. As of this writing, they’ve visited nearly 300 breweries, sticking mainly to the coast and the southern edge of the States.

“We quickly learned it was great way to meet excellent people and learn about the new places we were visiting,” Scarpello says.

Gary and Leeanne Boone retired from Ford Motor Co., and after five years of part-time RV travel, purchased a 40-foot 2003 Country Coach motor home, called “No. 1,” and pursued their dream life. Since starting full time in mid-2011, they’ve traveled the eastern half of the United States and Canada from Florida to Nova Scotia, and New York to Texas. So far, they have visited about 50 breweries as part-timers and more than 125 breweries since full-timing.

“Our primary motivation is seeing North America in a manner and depth that you can only do from the road,” Gary Boone says. “One thing we always did in our travels was to seek out breweries along the way.”

His list of breweries visited contains many familiar to those steeped in the craft beer world: Cigar City, Highland, Brooklyn, Ommegang and more. But in a reflection of the sheer numbers of small brewers in the nation, there are more names that might be unfamiliar to those outside the borders of their home turf. The Scale House in Ithaca, NY. Geaghan Bros Brewing in Bangor, ME. Roth Brewing Co. in Raleigh, NC (which has since been sold and reimagined as Gizmo Brew Works).

The Willmores did not start their journey together. Ben Willmore set forth from Colorado seven years ago in his 40-foot 1997 Prevost bus conversion, named “Location.” (As photographers, when people ask, they can say they’re on “Location.”) After an extended online relationship, Karen joined him in January 2010, and three years later they tied the knot in a Hawaii wedding. He’s been to all 50 states, and she says she “only has a few left.”

Ben Willmore has visited so many breweries that he “really can’t count that high.” “I’ve been to literally hundreds of breweries or brewpubs since living on the bus,” he says.

Though he doesn’t keep a list of specific breweries, for a time he kept track of each beer he tried in his favorite style—India pale ale. Karen Willmore surprised him one year by compiling the data into a 78-page book, with a photo of the beer, a one-line comment, and its rating on each page. Leafing through the book, Ben Willmore found a few that he rated 9.5: Coronado Islander, Firestone Walker Union Jack and Bell’s Two Hearted Ale, among them.

He’s still searching for his first 10. His wife calls it an “unending quest.”

]]>

Peter Bouckaert, a native Belgian and brewmaster at New Belgium Brewing Co.

By Heather Vandenengel

Early last June of 2012, Brian Purcell, CEO and brewmaster of the soon-to-open Three Taverns Craft Brewery in Decatur, GA, took a seven-day beer tour of Belgium with his wife. He and his partner and CFO, Chet Burge, had almost reached their funding goal to open a Belgian-beer-inspired brewery, and the trip served as inspiration—in more ways than one.

“While touring breweries, I started to have this vision for bringing a Belgian brewer to the U.S. to work for us,” he says, calling from the brewery, which in early April was still a construction zone.

“I felt like there’s something in the DNA of Belgian brewers that you just can’t reproduce in an American brewer. At least it’s very hard, and I wanted to make as authentic Belgian-style beers as we can make, with an American creative twist or flair.”

Brewing Belgian beers had become an obsession for Purcell. As a homebrewer of 10 years, he dedicated himself to mastering Belgian-style brewing and learning as much as he could about Belgian beer. After four years of planning, his production brewery brewed its first batch in June.

“I learned that there are techniques, sensibilities, a philosophy or approach that Belgians have for brewing that is unique to that country, and I wanted to learn that and I wanted to discover it more,” he says of his Belgian trip.

Purcell’s pursuit—to bring a Belgian brewer to America to brew the best Belgian-inspired beer possible—raises questions of origin and its influence. How much does a brewer’s native culture influence his brewing? And what happens when a brewer makes beer in a brewing culture far different from his or her own?

The global brewing scene has become a melting pot, or mash tun, of beer cultures, styles and techniques. While Americans have always taken inspiration from other cultures and brewed styles that originated abroad, the relationship has grown stronger and shifted in a different direction. More and more, American brewers are drawn to the wild side of Belgian brewing, even investing in koelschips and isolating native yeasts, while some small Belgian brewers are brewing American-style IPAs and coming to the U.S. to brew collaboration beers.

It’s cross-cultural beer pollination, and nowhere is this more clear than in the stories of the pioneers—the brewers who were born, raised and trained in Old World brewing cultures of Belgium, Germany and the United Kingdom and then came to brew in the States. While backed by tradition, they’re inspired by the potential for change and the chance to be immersed in America’s craft beer culture. Here are a few of their stories.

]]>